1. Introduction

Tango is a form of music written in the tradition of Western major-minor tonality, a system of relationships between tones (organized as scales), chords (tones sounding conjointly), and functions (usage) of chords. Together, scales and chords make up a key, and we speak of a composition as being in C-major, for example, when it is built on a C-major scale and the chords resulting from that scale. Likewise, a piece is said to be in a-minor if it uses the a-minor scale and chords.

If one asks a musician how

the key of a composition is determined, one will frequently hear that

the scale and the chord on which the piece ends are the indicators of

the key. This will be true in most cases, but it is ultimately not a

correct statement. Using a C-major scale and ending on a C-major

chord does not mean the piece is “in” C-major. In order to be

“in” C-major, the other chords in the piece must be in certain

relationship to the C-major chord. This is the principle of tonality

(hence, major-minor tonality), and harmony provides a set of rules by

which tonality is expressed.

We will here focus on two

fundamental rules of harmony:

- a tonal composition has one fundamental chord, the tonic, to which all other chords progress and resolve to;

- as the tonic constitutes a point of repose or arrival in a piece of music, the dominant is its counterpart, expressing tension with an implicit need for resolution to the tonic.

The tonic is represented

by the lowest tone of the scale and the chord built on it. This

corresponds to the musician's notion of “key” mentioned above,

that is, a scale (which starts with the tonic) and the final chord of

the piece. The tonic being the first degree of the scale, it is

customarily indicated in harmonic analysis by the Roman numeral I.

The dominant is the chord

build on the interval a fifth (five scale steps) above the tonic. It

is the counterpole of the tonic, implying a need of resolution to the

tonic. The harmonic progression from the dominant to the tonic is the

most common way to establish the tonic as the tonal center of a

piece. In harmonic analysis, the dominant is customarily indicated by

the Roman numeral V.

Composers did not select

the relationship between tonic and dominant to harmonize their music

by arbitrary choice. It is, rather, founded on the human perception

of music. We tend to perceive a descending movement to the tonic as a

resolution of tension.

Example 1: Ascending and descending major scale

Likewise, the harmonic

progression from the dominant to the tonic (indicated in the last two

measures if the following example by the Roman numerals V and I,

respectively) conveys a sense of arrival and repose.

Example 2: Harmonic progression in C-major

The preceding example

exhibits a harmonic progression that is frequently encountered in

tonal music: a cadence. A cadence is a harmonic-melodic formula used

to impart a sense of resolution and finality. It is typically applied

at the end of a composition. Every tango dancer knows—or should

know—the final “chan-chan” of a tango with which the dance

terminates. Musically speaking, it is a cadence, the final one, and

thus the strongest one in a tango. Woe betide the dancer who

continues to move after the “chan-chan”!

But cadences do not only

appear at the end of a piece. They are also utilized in many different

forms to delimit phrases and melodies, where they function as points

of arrival or transition. It is precisely through cadences that the

tonality of a piece is articulated.

2. Arturo De Bassi's El

Incendio

As an example of a

classical instrumental tango, let us turn to El Incendio

by Arturo De Bassi. (There are three recordings by Rodolfo Biagi, Juan D'Arienzo, and

Carlos Di Sarli, respectively, that are still played intermittently in milongas

today.)

Arturo De Bassi grew up in a musical family. At age thirteen, in 1903, he joined the orchestra of the Apolo theater in Buenos Aires as a clarinetist. Three years later he composed his first tango, El Incendio (“The Fire”). It was inspired by the warning signals of the fire brigade. (Sirens for the horse-drawn vehicles had not yet been invented. It seems that in Buenos Aires bugle calls were used instead.) De Bassi, who claimed to have sold some 50,000 copies of the score, published the piece himself with great success, leaving it in music stores on consignment.

3. The Formal Division

El Incendio

consists of three sections (hereafter labeled A, B, and C,

respectively), which is a form typical for instrumental tangos of the

first quarter of the 20th century. The third section was

often designated a “trio” and was composed in a character

different from the other sections. The “trio” designation was

omitted in the score of El Incendio,

but the section has nevertheless been composed in such a way that it

marks a contrast against the other two sections. Sections A and B,

for example, begin with melodies in the high register, then showing a

descending melodic movement. Section C, on the other hand, begins in

a low register with an ascending motion.

|

| Example 3: El Incendio, section A, melody descending from high register |

| |

|

| |

|

The three parts of a tango like El Incendio were not simply played in succession from A to C. Rather, sections were repeated, yet not necessarily in order. The order of play may or may not have been indicated by the composer in the score, but even if it was, the performers were not bound by it. In fact, different recordings show great variety in the order in which the ABC sections could be performed. In the case of El Incendio, however, most recordings show the standard repetition scheme of a three-part composition: section A was played at the beginning and repeated after each of the following sections, thus resulting in a pattern A B A C A. (This pattern is also followed by Firpo in the example of the complete recording given below.)

4. A Simple Harmonic Analysis

The

music examples given below are taken from a piano score of El

Incendio and a recording made in 1927 by Roberto Firpo and his

orchestra, respectively. There are differences between the piano and

the orchestra scores, but these do not affect the points of the

argument presented here.

The

harmonic analysis is kept to a minimum and only aims to demonstrate

the synergy between tonic and dominant. Below each stave of music,

the key of the example is indicated by a capital letter (F or C,

respectively). To the right, the occurrences of tonic and dominant

are indicated by Roman numerals, I or V, respectively.

Each section

of El Incendio is a self-contained unit with a distinct

melody of 32 measures length and a strong cadence at the end. The

first section, A, shows a key signature of F-major, which identifies

the corresponding scale used in this section. Furthermore, F-major is

also the final chord.

Example 6: El Incendio, section A

Sections

B and C differ from A in one important aspect: they are not written

in F but in C-major. This is evidenced not only by the key signatures

and final chords. The harmonic movement within these sections shows

the same kind of oscillation between tonic and dominant as in Section

A—only in C-major.

Example 7: El Incendio, section B

Example 8: El Incendio, section C

Thus

having three sections with two tonalities, the question arises: is El

Incendio “in” one

particular key, or does it have two? If it is one key, which one is

it? The answer to this question lies in the pattern of repetition

with which the piece is performed. Section A being in F-major, and B and C

being in C-major, it turns out that the piece starts and ends in

F-major, and that the two sections in C-major are excursions, as it

were. The unfolding of the tonality could be represented as follows:

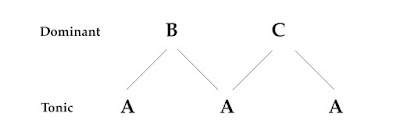

|

| Example 9: El Incendio, tonic/dominant relationships between sections |

Harmonically,

F-major is the starting point of the piece as well as it is the point

of resolution following the C-major sections. The relationship of B

and C to A is a clear example of dominant and tonic, that is, the

resolution from tension to repose. In conclusion, we may

unequivocally state that El Incendio

is written in a key, and that the key is F-Major.

It

is important to note that the rules of tonality apply to all levels

of the composition. The association of tonic and dominant governs the

harmonic development within each section, just as it determines the

relationship between the sections. Thus, the formal layout of the

piece mirrors the harmonic organization of the individual sections.

The formal and harmonic

layout of El Incendio is neither an original invention of De

Bassi, nor is it particular to tango. In fact, it is one of the most

common ways to structure instrumental compositions in Western music.

5. Assessment

De

Bassi's El Incendio is a delightful composition that has not

lost its charm in the more than 100 years of its existence. The

interpolation of the signal fanfares into the melodic fabric is witty

and makes the piece instantly recognizable. Moreover, the composition

is formally and harmonically well balanced and appealing at the same

time. A remarkable composition for a sixteen-year-old!

Without

repudiating the composer's accomplishments, it must be said

nevertheless that the formal and harmonic layout of El

Incendio is not original with De Bassi. Nor is it particular to

tango music. It is, in fact, one of the most common ways to structure

instrumental compositions in Western music. Rather, it demonstrates

that Arturo De Bassi, scion of musicians in Buenos Aires, had been

well trained in the family business.

----------------------------

Example 10: El Incendio, performed by Roberto Firpo and his orquesta típica, 1927

No comments:

Post a Comment