|

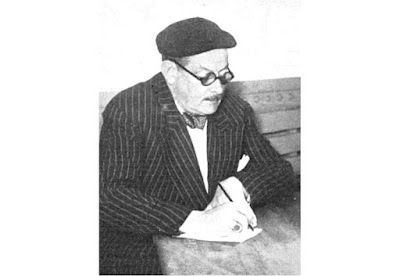

| Osvaldo Fresedo |

(Deutsche Version)

Those who have taken a closer look at classical music will remember the sonata form. It is a compositional model that is characteristic and typical of the music of the “classical” period. At closer examination, however, one cannot escape the impression, however, that while composers—especially the imaginative ones—made extensive use of the model, they nevertheless wanted to show again and again that there were other ways of composing and, thus, abated the model. It is precisely this point that makes their music interesting, that is: an expectation is created but it remains unfulfilled and is replaced by something unexpected and surprising.

Those who have taken a closer look at classical music will remember the sonata form. It is a compositional model that is characteristic and typical of the music of the “classical” period. At closer examination, however, one cannot escape the impression, however, that while composers—especially the imaginative ones—made extensive use of the model, they nevertheless wanted to show again and again that there were other ways of composing and, thus, abated the model. It is precisely this point that makes their music interesting, that is: an expectation is created but it remains unfulfilled and is replaced by something unexpected and surprising.

What makes a tango a

tango? In order not to get lost in an abyss of countless

possibilities, let us render the question more precisely: What

characterizes a “classical” Argentinian tango? The question

cannot be adequately answered by referring to musical form, since

tango is based on simple song forms that are used “universally”

by other musical genres as well. Neither does the orchestration, the

orquesta típica, provide

a better answer since the orchestration is not more than a decoration

of the music. Orquestas típicas

(see Rodríguez, Carabelli, Canaro, for example) readily performed

pieces of other genres that did not thereby turn into tangos.

The

subject being still too extensive, let us limit our investigation,

therefore, to two aspects that could be called characteristic, since

one will find them in almost all tangos. The first one is a

rhythmical figure, the síncopa;

the second is a stylistically formative principle in which formally

related sections of a piece are set off against each other.

The síncopa

Syncopation

is a rhythmical procedure in which one or more notes, which normally

appear on accented parts of a measure, are played on unaccented ones

and help over to a following accented part of the measure.

Syncopation can extend over more than one measure but in tango, a

characteristic short figure—the síncopa—can

be heard in almost every piece. (For this reason, we use the Spanish

term síncopa in

order to refer to this special context in tango.)

Here

is an example. In the customary 2/4 time signature of tango, a

typical síncopa could be notated as follows:

The arrows above the stave indicate the accented parts of the

measures. It follows from this, that the outer notes fall on accented

parts of a measure, however, while the inner ones fall on unaccented

parts. Musically, it sounds as follows:

During the first three decades of the 20th century, the

composers of the guardia vieja employed the síncopa

abundantly and sometimes constructed entire melodies out of this

figure. The first melodic theme of Roberto Firpo's tango La

Bordadora, in which the síncopa appears five times, may

serve as an example.

|

La

Bordadora (Roberto Firpo): A simplified rhythmical representation

of the first melodic theme. The square brackets below the stave

indicate the síncopas.

|

Musical

Contrast as a Stylistically Formative Principle

Musical Contrast as a Stylistically Formative Principle

The structural composition

of a tango remains within the framework of simple musical forms.

Normally, it consists of three melodies of 16 measures that are

repeated and varied in one form or another. The musical interest of a

piece lies largely in the implementation of the repetitions. The

orchestras of the heyday of tango understood to invigorate the simple

musical forms through variations in execution and orchestrations to

such a degree that the pieces—in spite of their limited

material—never appeared boring. Variety and contrast are

a stylistically formative principle: If a melody or part thereof is

played at first one way, then the continuation or repetition will be

rendered in a different manner.

Variety and contrast can

be expressed in a great number of ways: in the orchestration (violins

are set against the bandoneons or the piano), the sound register (a

melody appears in a high voice, than in a low one), the articulation

or phrasing of a melody, etc. The alternating rendition of a melody

as long or short note values is—like the síncopa—a

typical component of tango.

(Executed by the violins,

“long note values” means that the bow remains on the string and

is pulled through over the whole length of the note. With “short

note values”, the bow does not remain on the string, but only

strikes it and is immediately taken off the string again. The

difference between the two ways of playing is a different quality of

sound.)

Let

us look at Aromas, a

tango by Osvaldo Fresedo, as an example. (We are referring here to

Fresedo's recording of 1939 with the singer Roberto Ray.) The piece

consists of three melodies of 16 measures and their repetitions. Each

melody is made up of two eight-measure phrases that as opening and

closing subsections define the melody as a unit. In order to

differentiate the melodies and their phrase parts, we shall call them

1 A and B, 2 A and B, and 3 A and B, respectively.

Theme

1, part A, is played throughout with long note values, that is, “on

the string”.

| Fresedo Aromas, 1 A |

Theme

1, part B, shows a mirror symmetry between the eight-measure phrases.

The first phrase starts out with short “hammered” notes and ends

with long ones played “on the string”. The second phrase begins

with long note values “on the string” and ends with short ones.

| Fresedo Aromas, 1 B |

In theme 2, part A, the

first phrase starts off with

short “hammered” notes and ends with long ones “on the string”.

The second phrase repeats the arrangement of the first.

| Fresedo Aromas, 2 A |

The

first phrase of theme 2, part B, is played entirely in long note

values, the second phrase entirely with short ones.

| Fresedo Aromas, 2 B |

Theme 3, parts A and B,

show a freer alternation of sections with long and short note values.

Nevertheless, they have been distributed in such a way that they

reflect the internal structure of the theme.

| Fresedo Aromas, 3 A |

| Fresedo Aromas, 3 B |

As

a diagram, the phrases executed as series of long and short note

values could be presented as follows:

|

| Fresedo Aromas, schematic view of the orchestration |

Two

conclusions can be drawn from the diagram above. First, the

orchestration follows the internal structure of the melody, that is,

the change between notes played “on the string” or “hammered”

occurs at intersections of melodic units (consisting of two, four,

eight, or sixteen measures). The structure, the form, of the musical

piece is thus made audible. Second, the distribution within the

eight-measure phrases reveals an architectural symmetry, especially

in the first two phrases. This indicates planning and suggests that

the arranger wanted to exploit the contrast of “long” and “short”

note values as a means of musical expression.

Fresedo's Sueño azul

The

above example for stylistically formative elements in tango have been

chosen because they demonstrate the points under discussion better

than other pieces. One should not expect every piece to follow the

same model, however. The music would be rendered uninteresting as it

would lack an element of surprise. With a little practice the

listener of tango will soon pick out the síncopa in every

tango and recognize contrasting orchestrations in the repetitions of

melodies even if they are not expressed differently as long and short

note values.

Nevertheless,

one can find again and again pieces that refuse categorization.

Musicians, as creatively thinking artists, often seem to prefer

disarray over systematic planning. Fresedo's Sueño azul is a

piece that appears to lack completely what has been described above.

It was recorded two years before Aromas. The full, mellow

sound of the strings, the harp, and the voice of Roberto Ray readily

suggest that they belong to the same style period. The first

impression of the sound quality admits no doubt that the orchestra of

Sueño azul is the same one that is performing in the

recording of Aromas.

Yet,

Sueño azul differs from Aromas in two important

points. In the former the orchestration remains the same all

throughout the piece: the violins play the melodies continuously “on

the string”. Even when they accompany the singer and recede into

the background while playing a counter melody to the voice, the

articulation remains soft and joined. The contrast between long note

values “on the string” and short, “hammered” notes is

completely absent. Not even a síncopa can be discerned. The

only moment that recalls a síncopa comes at the end of the

first phrase in the eighth measure. It is, however, not a síncopa

but a triplet.

Is

that still tango? By name it is, but it is not Argentinian! The music

of Sueño azul was

composed by an Hungarian musician, Tibor Barciz, to a French text.

The original title was Vous, qu'avez-vous fait de mon

amour?. The piece premiered

1933 in Paris in a theater revue by Henri Varna, Vive

Paris!. It was a successful

composition that was repeatedly recorded by various orchestras for

years to come (see versions by René Juyn and the Grand Orchestre Perfectaphone [1933], Tino Rossi and the Orchestre M. Pierre Chagnon [1934] and Jean Lumière [1934] ).

With

an Argentinian tango, Vous,

qu'avez-vous fait de mon amour?

has little in common. It is a strophic song with an underlaid

habanera rhythm and a síncopa

at the end of the phrase in the eighth measure.

Vous, qu'avez-vous fait de mon amour?, Jean Lumière

It

is well known that the habanera rhythm as a repeated bass pattern is

the basis of one of the three tango dances, the milonga. Not only

that, it also appears occasionally in (Argentinian) tangos. In fact,

it was quite common ten or twenty years before the composition of

Vous, qu'avez-vous fait de mon

amour?. Such tangos were usually

labeled “tango milonga” (see Roberto Firpo's El

amenecer, Francisco Canaro's

Charamusca,

or José Padula's Nueve de Julio, for example). From the 1930s on,

however, the habanera rhythm in these pieces was hardly played

anymore in these pieces. That is, the notated dotted rhythm was “normalized” to

straight, “un-dotted” notes in the arrangements. (For example,

listen to di Sarli's version of El

amenecer.) From an Argentinian

perspective of the 1930s, the use of the habanera rhythm in Vous,

qu'avez-vous fait de mon amour?

seems a bit old-fashioned.

Furthermore,

in the Argentinian “tango milonga”, the habanera rhythm was used

as a means of stylistic contrast from one section to another,

corresponding to the alternating sections of long and short note

values discussed above. In the French recordings of Vous,

qu'avez-vous fait de mon amour?,

however, the habanera rhythm is used continuously throughout the

piece, that is, without differentiation from section to section. Such

an application of a rhythmical patter it not typical of Argentinian

tango, but rather of European dance music. The “Argentinian”

stylistic elements in the French recordings are, then, no more than a

template.

When

Vous, qu'avez-vous fait de mon

amour?

was published with a Spanish text as Sueño

azul

in Argentina, the publisher did not simply call it a “tango”, but

a “great Hungarian tango”. Since the piece had been very

successful in Paris, it does not as a surprise that an Argentinian

musician like Fresedo took it into his repertoire. Yet, one wonders

why he avoided any musical reference to tango—which, after all, was

his métier—and did not arrange it in a more “authentic”

(Argentinian) manner.

(© 2017 Wolfgang Freis)