|

| Eduardo Arolas |

1. Introduction

1.1 Minor Keys

Heretofore,

we have explored two fundamental aspects of tonality: the

relationships of the dominant and subdominant to the tonic. We have seen how dominant and

subdominant functions were employed to establish a tonality and to

provide a musical contrast to the tonic in order to make a

composition more interesting. For reasons of simplicity, so far we

discussed pieces set in major keys. However, there exists another

kind of tonality that is particularly important to tango: the minor

keys.

Major

and minor keys are distinguished by different types of scales, that

is, the distribution of whole and half tone steps varies. As a

consequence, the harmonies are diverse as well. The chord built on

the tonic, for example, corresponds to the designation of the key and

is either major or minor.

All

major and minor scales consists of five whole tone and two half tone

steps. In a major scale, the half-tone steps are located between

third and fourth as well as between the seventh and eighth scale

degree. (In the following examples, half tone steps are indicated by

curved brackets above the respective notes. The tonic chord is played

at the end of each example.) The sequence of half and whole tone

steps in a major scale remains the same in ascending and descending

motion.

In

a (natural) minor scale, the half-tone steps are located between the

second and third as well as sixth and seventh scale degrees.

It

is the location of the first half-tone step that renders the tonic

chord major or minor. Being located between the third and fourth

scale degrees in the major scale, the tonic chord is necessarily a

major chord. Correspondingly, since the first half-tone step is

located between the second and third scale degrees in a minor scale,

the tonic chord will be a minor one.

It

is a particularity of the minor scale, however, that it is rarely

used in its natural state. For melodic and harmonic reasons, the

sixth and seventh degree are raised by a half step in ascending

melodic motion, and lowered again in descending motion. This kind of

scale is commonly called the “melodic minor scale”.

It

becomes apparent from the example that the harmonic possibilities of

a minor key are greater than those of a major one. For example: in a

major key, the subdominant and dominant are always major chords. In a

minor key, however, they can appear as major or minor chords,

depending in what scalar context they occur (that is, ascending or

descending melodic motion).

1.2 Relative Major-Minor Keys

Major and minor keys that share the same key signature are called relative keys. Their relationship is obvious: the chords built with the natural scales are common to both keys. Yet, tonic, subdominant and dominant are different in each key and hence their tonality is distinct. The following example shows the scale degrees of the relative keys F-major and d-minor. The tonic degree is indicated by square boxes, the subdominant and dominant by brackets above or below the degree numerals, respectively.

|

| Relative major and minor keys: scales. |

The

example illustrates that relative keys are similar inasmuch as they

share a common body of sound material, that is, the chords. On the

other hand, they are distinct entities because the chords function

differently in relationship to the respective tonic. For example, the

dominant of the minor key (d: V in the example) can only be a

secondary dominant in the major key (F: III in the example). The

interrelation between tonic and dominant is fixed and particular to

just one key. (Secondary dominants were discussed in A Brief Harmony of Tango, II.)

We

have seen in our previous discussions of harmony in tango music that

composers used the dominant and subdominant keys as a musical

contrast to the tonic key. It was done in order to emphasize the

formal structure of a piece and to make it sound more interesting.

Both the tonic and the contrasted tonality were major keys in these

cases. One will also find major and minor keys used in such fashion.

This was, in fact, a method used by composers more frequently than

setting up a contrast between keys of the same kind.

The

reason for this preference seems to be that a contrast between major

and minor keys is more perceptible on the one hand and, on the other,

the harmonies become richer and more expressive through minor keys.

In addition, the different sound quality of a cheerful major and

somber minor key lent itself especially well to express the

melancholy mood of many tango song texts.

2. Arolas, “El Tigre del Bandoneón”

Many

tango dancers today may not be familiar with the name Eduardo Arolas,

but undoubtedly they will recognize a good number of his

compositions. There is no milonga where one will not hear tangos like

“Comme il faut”, “Derecho viejo”, “Retintín”, “La

guitarrita”, or any other of Arolas' many compositions.

Arolas

was highly respected by his peers both as a bandoneonist and

composer. Born in 1892 in Buenos Aires, he died at the young age of

32 in Paris. Consequently, there exist comparatively few recordings

of Arolas and his orchestras, and those that are extant are primitive

audio recordings of poor quality—hence his inconspicuous fame

today.

His

first instrument was the guitar, which he played in the cafés of his

hometown, but he soon switched to the bandoneon. When he composed his

first tango, “Noche de garufa”, in about 1909 he was still

musically illiterate and his friends had to write down the music for

him. In 1911, however, he entered a conservatory and studied music

for three years. The knowledge he gained in music theory greatly

influenced his music. His pieces—and Cardos

among them—attest a composer with a solid understanding of

music theory and an alacrity for experimentation.

3. “Cardos”

A

biographer of Arolas counted Cardos among the composer's

“unknown” pieces. We have encountered only two recordings of it,

one of them being the superb version by the Orquesta Típica Victor

given below as an example. Showing no traces of the habanera rhythm,

the piece appears to be a late composition by Arolas, having been

composed most likely in the 1920s.

Like

most instrumental tangos of the first quarter of the 20th

century, Cardos

is a three-part composition. Its structure is very regular: each of

the three sections (referred to hereafter as A, B, and C,

respectively) is 16 measures long. In turn, each of the sections is

divided into antecedent and subsequent phrases of 8 measures.

This

division continues on even smaller levels: each eight-measure phrase

breaks down into two periods of four measures which are again divided

into motifs of two measures length. The two-measure motifs are the

smallest melodic units that express a musical idea. Each four-measure

period ends with some kind of cadence; those occurring at the end of

the consequent phrases are emphasized and articulated

stronger.

Sections

A and B are written in d-minor, as is indicated by the key signatures

and final chords. In both cases, the final chord is preceded by a

strong cadence that anchors the tonality firmly in d-minor. Section

C, however, which shares the same key signature, ends on an F-major

chord. This final chord is also preceded by a strong cadence and thus

this section is written in F-major, which is the relative major key

to d-minor.

If

the piece is performed with all its repetitions (see the video with

the performance of the Orquesta Típica Victor below), the tonal

structure unfolds as follows:

The

formal layout and the tonal relationships between the sections are

quite conventional. Apart from being set in a different key, section

C, the trio, is surrounded by the other section through repetitions.

Looking at the piece as a whole, it begins and ends in d-minor but

turns to a contrasting key (for musical variety) in the middle. This

contrasting key is not the dominant or subdominant; in this case it

is the relative key F-major.

We

have stated above that it is a characteristic of relative major and

minor keys to have several chords in common. As a consequence, it is

easy to move harmonically from one relative key to the other. That is

to say, it is but a small degree of change that may hardly be noted.

Yet, if the demarcation between relative major and minor keys is

weak, then there is room for ambiguity. This ambiguity is exactly

what Arolas brings forward to make his piece interesting. Unlike the

straightforward, rather conventional large-scale layout of the piece,

the harmonic development within each section is much more involved

and engaging.

3.1 Section A

It

was observed that the formal division of Cardos

is very regular. Each section consists of sixteen measures that, in

turn, are divided into two phrases of eight measures length, and so

forth.

The

antecedent phrase of section A demonstrates the division into

four-measure periods most clearly since the second period is

identical to the first; measures 5 to 8 are simply a repetition of

measures 1 to 4.

|

| Cardos, Section A, Antecedent Phrase |

The

second phrase echos the melodies of the first one with different

harmonies and without repetition. The division into four-measure

periods is nevertheless maintained.

|

| Cardos, Section A, Subsequent Phrase |

Cardos, Section A

In

terms of tonality, the two phrases of the section differ

significantly. Looking at the antecedent phrase by itself, it is not

clear in which key it is written. The two four-measure periods (which

are identical) consist of two simple motifs built on an F-major and

d-minor chord, respectively, and their dominants. The harmonies can

be interpreted either as being in d-minor or F-major. If it is in

F-major, then the phrase starts on the tonic (I), which is common way

to start a piece. If it is in d-minor, then the antecedent phrase

ends on the dominant (V), which is a typical way to end an antecedent

phrase. Hence, the tonality in this phrase is left ambiguous.

The

following example (the music being reduced to chord progressions)

shows the harmonic analysis in both d-minor and F-major.

|

| Cardos, Section A, Antecedent Phrase, harmonic reduction |

In

the consequent phrase, however, the tonality becomes unambiguous.

Both periods end with a dominant cadence on d-minor (V-I, see

measures 3-4 and 7-8, respectively).

|

| Cardos, Section A, Consequent Phrase, harmonic reduction |

In

summary, the section starts with an antecedent phrase that is tonally

ambiguous, whereas the consequent phrase is firmly establishes

d-minor as the key.

Cardos, Section A, harmonic reduction

3.2 Section B

It was a striking feature of section A that the antecedent phrase consisted of two periods of which the second was an exact repetition of the first. A similar scheme can be found in section B. Here, however, the repetition involves the complete phrases. Moreover, the motifs are involved in another kind of repetition: a sequence. All two-measure motifs are similar; yet, they are not literal repetitions, but are shifted down to a different scale degree.

|

Cardos,

Section B, Antecedent Phrase

|

The

consequent phrase repeats the preceding one almost exactly and only

changes melodically at the end to emphasize the cadence.

|

Cardos,

Section B, Consequent Phrase

|

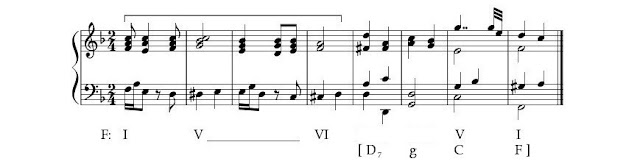

The

first period (measures 1 to 4, two motifs of the sequence) contains a

harmonic progression (D-g-C-F) where each chord is a fifth lower than

the preceding one. Hence, this progression resembles a series of

secondary dominants, where the preceding chord resolves to the

following one. And, since it is a series of dominant progressions,

there is no clearly defined tonic. Therefore, this sequence could

equally well be interpreted as being in d-minor or F-major. It is

only in the second period (measures 8 to 5) where the key is

established as d-minor through a strong cadence (measures 6 to 8).

Both

sections A and B are harmonically congruent, then. Both are set in

d-minor, but a clear articulation of the key takes place only after

passages that are tonally ambivalent.

Cardos, Section B, harmonic reduction

3.3 Section C

Section

C continues the pattern of repetitions set up previously. The two

motifs of the first period (measures 1-2 and 3-4, respectively) are

arranged as a sequence.

|

Cardos,

Section C, Antecedent Phrase

|

The

consequent phrase, as in section B, repeats the antecedent one almost

completely and only introduces some variation at the end in order to

emphasize the cadence.

|

Cardos,

Section C, Consequent Phrase

|

Cardos, Section C, harmonic reduction

Harmonically,

section C differs from the others inasmuch as it is less ambivalent

about its key. This is largely a consequence of being set in a major

key (F), which is more homogenous than a minor key. Another reason is

that one may consider both periods as extended cadences in F-major.

|

Cardos,

Section C, Antecedent Phrase, Harmonic Reduction

|

Starting

out on the tonic, the first period (measures 1-4) returns to d-minor,

however, by introducing a “deceptive cadence” in measure 4.

Deceptive cadences are a common feature in major-minor tonality. The

term describes a situation in which a regular dominant cadence does

not resolve to the tonic (V-I) as expected but to the relative minor

(V-VI).

The

second period (measures 5-8) reintroduces a harmonic progression that

we have encountered already in section B: it is the harmonic sequence

of secondary dominants, D-g-C-F. In section B, it appeared in the

first period of each phrase. Here, in section C, it appears in the

second period. The correspondence goes further: the first period in

section C ended with a deceptive cadence on d-minor. In section B it

was the second period that ended with a cadence on d-minor. In short,

we find that the composer recapitulated the harmonic progressions of

section B in section C by swapping four-measure periods.

Cardos,

Section C, Harmonic Reduction

4. Conclusion

Our analysis suggests that the tonal structure of Cardos has been carefully planned. Sections A and B are set in d-minor, whereas section C is set in the relative key, F-major. Sections A and B are tonally more involved in comparison to the clearly defined section C. The d-minor key is made explicit only after moving through harmonic progressions that are tonally ambivalent. Section C, by contrast, is unequivocally set in C-major from the outset. Thus, the tonal structure of section C, the trio, provides a polarity to the preceding sections.

Arolas' Cardos is a fascinating composition that surprises through its economy of means. The composer created a piece in which a few melodic and harmonic ideas are developed with great expressiveness. Cardos is the work of an experienced composer who planned his piece with care and consideration. Nothing in this piece appears by chance but has its proper place and function.

Arolas' Cardos is a fascinating composition that surprises through its economy of means. The composer created a piece in which a few melodic and harmonic ideas are developed with great expressiveness. Cardos is the work of an experienced composer who planned his piece with care and consideration. Nothing in this piece appears by chance but has its proper place and function.

Arolas'

fame as a bandoneonist is legendary but an estimation of his work as

a composer is still lacking. Cardos

shows one thing very clearly: he was a serious composer who should be

taken serious.

Eduardo Arolas: Cardos, Orquesta Típica Victor

© 2017 Wolfgang Freis

No comments:

Post a Comment