1. Introduction

Our

preceding article discussed how tonal harmony is established through

scales (key signatures) and harmonic progressions from the dominant

to the tonic (in the examples identified as V and I, respectively). (

See A Brief Harmony of Tango, I

for a discussion on key identification. In this article, we introduce two more concept of

major-minor tonality: the subdominant and secondary dominants.

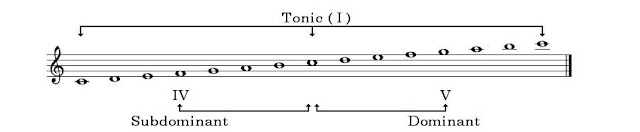

1a. The Subdominant

The

subdominant derives its name from its position in relation to the

tonic. Whereas the dominant is located a fifth (that is, five scale

steps) above the keynote of a scale, the subdominant has its place a

fifth below the tonic (or, by inversion, a fourth above—hence it is

identified as IV in the following examples).

|

| Example 1 |

The

subdominant commonly participates in cadences and appears before the

dominant. A typical progression would involve a move from the tonic

to the subdominant, the dominant, and finally return to the tonic

(I-IV-V-I, see the example below).

Another

typical application of the subdominant is the so-called “plagal

cadence”, in which a subdominant-tonic progression is appended to

dominant cadence ( … V-I-IV-I). This is a very common figure in

final cadences of church hymns.

Example 2: Cadences with subdominant

1b. Secondary Dominants

The

idea of a secondary dominant is simple: create a chord that functions

like a dominant to a chord other than the tonic. Turning a chord into

a secondary dominant requires an alteration of at least one of its

constituent tones. The resulting chord is not naturally found in the

key. It is, so to speak, a (temporary) dominant borrowed from another

key.

Secondary

dominants are employed to enrich the harmony of a piece and to build

up tension before the resolution to the tonic. A typical application

is to create a dominant to the dominant. Thus, the secondary dominant

resolves to the dominant, which in turn resolves to the tonic.

A

simple harmonic progression in a major key, with a dominant-tonic

cadence at the end, may sound as follows:

Example

3: Simple cadence (only dominant and tonic chords are

indicated)

To

enhance the sense of tension and resolution, one may precede the

dominant with its own dominant (indicated as V/V in the following

example). As can be seen the score, this chord is not set in its

natural form but has one pitch (the lowest one) raised by an

accidental. This raised tone acts as a leading-tone, that is, it

creates tension and thus implies the expectation of resolution to the

adjacent tone.

Example

4: cadence with a secondary dominant

As

was mentioned above, a secondary dominant can be applied to any

chord. Even secondary dominants may become the target of another

secondary dominant, as in the following example: from the second to

the fourth measure, we find four successive major chords. Each one is

the dominant of the following chord, thus resulting in a progression

B-Major – E-Major – A-major (dominant) – D-Major (tonic).

Example

5: cadence with two secondary dominants

2. “El Himno Bonaerense”

Angel

Villoldo's El

Porteñito,

is one of the best-known tangos. Composed in 1903, it was among the

first to be recorded. Villoldo called the piece a tango

criollo

but since the latter half of the 1930s, it has also been performed as

a milonga. Practically all Argentinian movies of the 1930-40s, set in Buenos

Aires around the turn of the 20th

century, included a dancing scene in which El

Porteñito

was performed, often at neck-breaking speed. If it is possible to

name one tango that represents Buenos Aires more than any other, it

is surely El

Porteñito.

3. The Formal Structure

The

formal structure of El

Porteñito

is simple and quite symmetric. It consists of three sections of 16

measures each (hereafter identified as A, B, and C). The three

sections are “through-composed” in the score, that is, they are

written successively without break and no repetitions are indicated.

Nevertheless, each section ends on a strong cadence that provides a

point of incision in the flow of the music and thus sets off one

section from the next.

Each

section is, in turn, divided into two phrases, antecedent and

consequent, of 8 measures (henceforth A1, A2, B1, etc.). Melodically

and harmonically, antecedent and consequent are very similar and

differ only in their terminations. Section A is characterized by

lively motives of fast note values in descending motion, leading to

short figures of the most characteristic rhythm of tango, the síncopa

(indicated in the examples by square brackets above the music stave).

|

| Example 6: Section A1, antecedent |

|

| Example 7: Section A2, consequent |

Example 8: Section A

The

antecedent and consequent phrases of section B are also very similar.

In contrast to section A, however, the rhythmic movement is calmer

due to longer note values and an almost complete avoidance of the

síncopa.

Example 9: Section B1, antecedent

|

| Example 10: Section B2, consequent |

Example 11: Section B

It

must be noted, nevertheless, that in terms of the fundamental

structure of the melodies, sections A and B differ little from each

other. The direction of the melodic movement is complementary

(descending) and the target notes of the descending motives

correspond as well. A comparison of the melodic outline of Sections A

and B demonstrates clearly the similarities between the two sections.

|

Example 12: Melodic outline of sections A and B

|

Section

C, by contrast, shows a predominantly upward melodic motion, and

there are no síncopas to be found.

|

| Example 13: Section C1, antecedent |

|

| Example 14: Section C2, consequent |

Example 15: Section C

As

the a melodic outline shows, the general movement strives upward and

thus creates a contrast to sections A and B.

|

Example 16: Melodic outline of section C

|

4. The Tonal Structure

As

mentioned above, a strong cadence demarcates the end of each section.

The final chord of these cadences corresponds to the key signature.

Furthermore, the division between antecedent and subsequent phrases

is also marked by cadences whose final chords coincide with those at

the end of the section. Thus, it is evident that the tonality of

sections A and B is D-major, whereas section C is set in G-major.

- Key SignaturePhrase:starts oncadences onFinal ChordD-MajorA1IV-ID-MajorA2IV-ID-MajorB1(I)V-ID-MajorB2(I)V-IG-MajorC1(I)V-I-IV-IG-MajorC2(I)V-I

All

cadences occurring at phrase endings are dominant-tonic cadences

(V-I), with one exception: phrase C1 ends with a plagal cadence

(IV-I). The importance of this singular occurrence is underscored by

the fact that all dominant-tonic cadences are strengthened by

preceding secondary dominants. Let us recall that the subdominant

(IV) is located at the interval of a fifth below the tonic (I). The

dominant (V), on the other hand, is located a fifth above. It follows

that a secondary dominant of the dominant is placed another fifth

above the tonic, etc.

Examining

the harmonic progressions that lead to the cadences in phrases A1 and

B1, for example, we find the following harmonic progression in the

last four measures: B-major, E-major, A-major (V), and finally D-major (I).

|

Example

17: Section A1

|

|

Example

18: Section B1

|

Describing

these progressions in reverse and in functional terms, we can say

that the tonic (I) is preceded by the dominant (V), by the dominant

of the dominant (E), and once again by another dominant (B). In this

way the passage preceding the cadence forms a sequence of secondary

dominants.

By

contrast, the harmonies of C1 remain within the limits of tonic and

dominant, but then at the end swing into the opposite direction to

the subdominant (IV) with the plagal cadence.

|

Example

19: Section C1

|

Looking

at the larger context in which this singular plagal cadence occurs

asserts that it did not come about by chance. Section C is the

equivalent of the “trio” section in other instrumental tangos.

Trios are customarily composed in a way that distinguishes them from

the other sections. We have noted earlier that C differs from

sections A and B in its melodic direction, which move upward in

contrast to the descending movement in A and B. Similarly, the

harmonic direction of C departs from the one encountered in the other

sections. A and B were characterized by harmonies on the dominant

side. C is in the subdominant key and exhibits at its midpoint the

only plagal cadence of the entire piece. Hence, it emphasizes

harmonies on the subdominant side.

5. The Repetitions

We

have noted earlier that El Porteñito is “through-composed”,

that is, sections A to C are written out in order in the score

without any indication of repetitions. Yet, compositions of this type

are always performed with some kind of repetition. A common way would

be to play sections A through C in order and then to repeat sections

A and B. Such an arrangement would highlight the contrasting

character of section C and lend a symmetrical structure to the piece

(ABCAB). A recording by the Quarteto Roberto Firpo (1936) expanded

this scheme by adding another repetition of all three sections (AB C

AB C AB).

Example 20: El Porteñito, Quarteto Roberto Firpo

One

will encounter a “standard” repetition scheme like Firpo's or a

variation thereof in most of the many recordings of El Porteñito.

Yet, tango orchestras appear to have been keen to record their own

versions of pieces, and two interesting versions of Villoldo's tango

with differing repetition schemes shall be mentioned here.

The

first one is a recording from 1928 by the Orquesta Típica Victor. (We invite you to pay special attention to the spectacular first violinist in this recording. Unfortunately, we do not know who it was, but it is likely to have been Elvino Vadaro or Agesilao Ferrazano, who performed with the Típica Victor in the late 1920s.)

Example 21: El Porteñito, Orquesta Típica Victor

Striking about this arrangement of El Porteñito is that it

starts with section C, thus, in the subdominant key. The complete

repetition scheme looks as follows: CABCA.

Francisco

Canaro recorded El Porteñito at least three times. In two of

these recordings, he followed the “standard” model, but one

recording with the Quinteto Pirincho from the 1950s is decidedly

different.

Example 22: El Porteñito, Quinteto Pirincho

In

this version, Canaro repeats all three sections in order: ABC ABC.

Thus, the piece ends in the subdominant key.

The

Victor and Canaro versions of El Porteñito raise the question

whether rearranging the three musical sections alters the formal and

tonal cohesion of the piece. A “standard” repetition scheme like

ABCAB follows the compositional logic: it articulates a musical idea

(AB, D-major), contrasts it with an opposing one (C, G-major), and

returns to the first idea. Both in terms of form and tonality, it is

clear what the original and the contrasting ideas are: the piece ends

where it started and thus presents a closed entity.

The

Victor and Canaro versions loosen the formal and tonal coherence. But

these performers were not the only ones to do so. It was quite common to

rearrange pieces and start or end them in the “wrong” key. No one

took exception to it. Pieces like El Porteñito were

well-known enough for the audience to quickly recognize a different

arrangement. The end justifies the means.

© 2017 Wolfgang Freis

No comments:

Post a Comment