Among compositions written

during the early part of tango history, there exist a number of

pieces that have been recorded by later tango orchestras as both

tangos and milongas. The different versions of some pieces will sound

familiar to the experienced tango dancer, perhaps without realizing

that these tangos are danced today in two different ways. Or, it may

instead come as a surprise that another version exists, not to be

danced the way it is customarily done today.

A striking example is El

Porteñito by Ángel Villoldo

(1861-1919), which most tango dancers will know as a milonga

performed by the orchestra of Ángel D'Agostino, sung by Ángel

Vargas. Yet, one can also hear it performed as a tango by the

orchestra of Juan D'Arienzo and—less frequently—by the Orquesta

Típica Victor, Canaro's Quinteto Pirincho, and Adolfo Pérez.

Villoldo himself defined El Porteñito

a “tango criollo”, not a milonga. In fact, Villoldo composed

hardly any milongas, and those have little in common with milongas as

we understand them today. The largest part of his output consists of

tangos—tangos with a variety of attributes besides “criollo”:

“argentino”, “nacional”, “milonga”. Later tango

orchestras recorded these pieces generally one way or another. For

example, the “tango milonga” El Esquinazo

and the “tango criollo” El Torito

were usually recorded as milongas, and the “tango criollo” La

Morocha as a tango. D'Arienzo

arranged the “tango argentino” Bolada de aficionado

as a milonga, but the “tango criollo” Yunta brava

he played as a tango.

We

repeat: The composer labeled all these pieces tangos. It will not

concern us here why orchestras chose to perform the pieces one way or

another. We simply accept it as a historic fact. We will suggest,

however, that the variant interpretations evince a conceptual change

of tango and milonga within the first four decades of the twentieth

century. We focus on compositions by Villoldo—the “numen of our

[Argentinian] popular music” (Francisco Canaro)—because they were

and still are widely known and his œuvre provides an ample source of

examples. The argument presented below applies to the work of other

composers as well.

1.

A Modern View of “Tango” and “Milonga”

Today,

tango is almost exclusively regarded as dance music. From that perspective, the milonga is distinguished from tango by having a

faster tempo and by having a continuous rhythmic foundation. The

rhythmic foundation is provided by a distinct rhythm that originated

from the Cuban “habanera”.

It

is this rhythm that forms the link between Villoldo's tango

compositions and their later arrangements as milongas. While the distinction of a milonga employing the habanera and a tango not using

it holds true for tango music from the 1930s on, this cannot be said

of pieces written during the first two decades of the twentieth

century. During that period, tangos used the habanera rhythm for

rhythmic accompaniment as well.

As

an example, we have extracted the lower part of a piano score of

Villoldo's “tango criollo” Don Pedro, which shows a use of

the habanera rhythm that is very similar to what one might expect of

a milonga. The tango consists of three sections (indicated as A, B,

C, respectively) that are played in the example without the customary

repetitions.

Villoldo, Don Pedro, excerpt, slow

The

habanera rhythm is prevalent throughout the piece. The only

difference to a milonga is the slow tempo. Were we to speed up the

tempo, the “tango criollo” could easily be danced as a milonga:

Villoldo, Don Pedro, excerpt, fast

Is

a milonga, then, simply a fast tango with the habanera rhythm as an

accompaniment figure? For many milongas of the 1930s and 1940s, such

a description would hold true. But, as we have pointed out already, some twenty years earlier,

the distinction based on the habanera rhythm could not have been

made. The rhythm was then prevailing in tangos

as well. Furthermore, it turns out that in the early days of

tango, the word “milonga” was commonly associated with poetry and

song rather than with dance music or a specific dance.

2.

“Criollo” Music

The

development of tango runs parallel—luckily—to the development of

music recording. At the beginning of the 20th century,

Argentina did not have a music recording industry. However, foreign

companies from the United States and Europe sent engineers to Buenos

Aires who recorded local musicians. These recordings were sent back

to the factories in the US or Europe and manufactured into records.

The recording companies then shipped the records (together with other

recordings from their inventory) back to be sold in Argentina.

In

order to distinguish Argentinian recordings from foreign ones, the

former were customarily referred to as the “repertorio criollo”.

The adjective “criollo” was employed to identify music pieces and genres that originated in Argentina or the countries of the

River Plate region. Tango and milonga were part of this body of

“native” music, which included a great number of song (estilo,

décima, vidalita, triste, etc.) and dance forms (pericón, gato,

zamba, chacarera, etc.).

Before

the advent of radio in Argentina, the larger record companies

advertised their new releases in newspapers and magazines. While

advertisements are not sales records or stock lists, they do give an

insight into what kind of music the orchestras played and was

listened to by the audience. At the very least, music record

advertisement shows what kind of music the recording companies

thought would resonate with their customers. The following

advertisement of the North-American record company Victor, published

in November 1906 for records to be sold at the Cassels department store in

Buenos Aires, announces the arrival of a “new criollo catalog”

that had been recorded three months earlier.

|

| Advertisement Cassels & Co., Buenos Aires, 1906 |

The

total list of more than 140 pieces consists of “songs, recitations,

tangos, national arias, orchestra and [wind] band pieces, etc.”.

Milongas are not mentioned;

but there is one tango in the itemized

list: Villoldo's El Porteñito, sung by Mrs. de Campos to the

accompaniment of an orchestra. There is

no particular mention of dance music, but songs and pieces performed

by bands and orchestras could, of course, include dances.

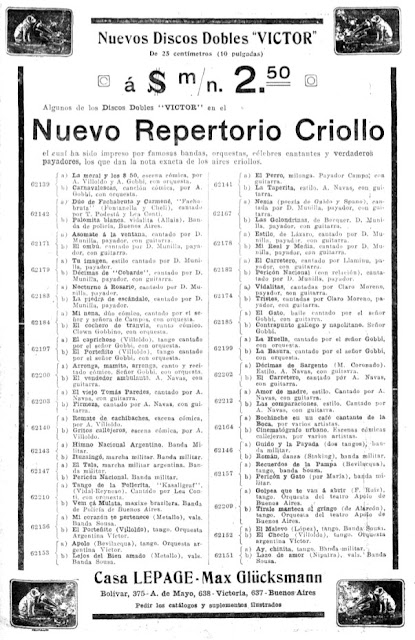

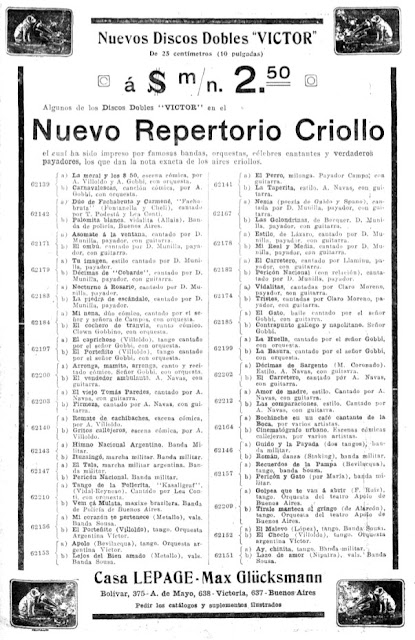

A

more extensive and detailed list—also by Victor—is given in the

following advertisement of the Casa Lepage of Max Glücksmann,

published in 1909. Glücksmann was a key figure in the development of

film and music in Argentina. He had acquired Casa Lepage, the company

of his former employer, in the preceding year. Like no other, he saw

the business potential for “criollo” products and was

instrumental in the promotion of tango. (In a later interview, he

stated that he was very proud of having made three men very rich:

Roberto Firpo, Francisco Canaro, and Carlos Gardel.)

|

| Advertisement Casa Lepage of Max Glücksmann, Buenos Aires, 1909 |

Like

the advertisement of 1906, the list consists largely of vocal music (30 double-sided records). The largest group of pieces is made

up of songs accompanied by guitar (24 pieces). Among “estilos”,

“décimas”, etc. there is also one milonga, El Perro, sung

by a “payador” (itinerant singer).

Moreover,

the list includes also 13 tangos. Three are sung with orchestra

accompaniment by Alfredo Gobbi (Villoldo's El Porteñito and

El Caprichoso) and Lea Conti (Tango de la Pollerita),

respectively. Five tangos were recorded by the Orquesta Argentina

Victor (Villoldo's El Choclo and, again, El Porteñito,

as well as Bevilacqua's Apolo) and the orchestra of the Apolo

Theater of

Buenos Aires (Ruiz, Golpea

que te van a abrir and Alarcón, Tirale

mateca al gringo). Five more tangos are performed by wind bands (two of them were recorded—most likely in the United States—by the wind band of

John Philip Sousa).

The

types of music present in the list could be categorized into three

groups. The largest group consists of songs with guitar

accompaniment. Wind bands and orchestras make up another group; it

includes most of the tangos and some valses and thus comes closest to

dance music. The third group is perhaps best described as music for

the stage, that is, music that would be performed in a theater,

varieté, or cabaret. There are comic songs and scenes sung by Ángel

Villoldo and/or Alfredo Gobbi, recitations, and music numbers from

plays. There are also actors among the performers. Lea Conti and

Arturo de Nava were actors of the troupe of the Podestá family.

Conti, in fact, was married to Antonio Podestá, who is credited to

have been the first to compose tangos for the theater (some of them

undoubtedly sung by his wife). Arturo de Nava also acted with the

Podestá troupe as a galan and tango dancer.

Two

events in 1912 changed the course of tango history: tango became a

fashionable dance in Paris, and the German recording enterprise

Lindström opened the first record manufacturing plant in Argentina,

making Max Glücksmann the exclusive representative for its Odeon

label. The developments in Paris popularized tango also in Argentina,

which led to the emergence of the “orquesta típica”—a

standardized small orchestra consisting of violins, bandoneons, bass

and piano—that performed tango music. Glücksmann took the best

musicians under contract: at first Roberto Firpo, then Eduardo

Arolas, Carlos Gardel, Francisco Canaro, etc.

|

| Advertisement Casa Lepage of Max Glücksmann, Buenos Aires, 1914 |

The

music is not specifically advertised as dance music but it is clear

from the repertory that the orchestras specialize in this kind of

music. Most pieces are tangos, followed by a handful of “vals”

and a few North-American dances—yet, no milongas.

|

| Advertisement Victor Talking Machine Co., Buenos Aires, 1917 |

In

the course of the second decade of the 20th century, tango

developed a stronger identity as dance music. The “repertorio

criollo” in the example appears divided into vocal and dance

pieces. Wind bands and symphonic (theater) orchestras are replaced by

“orquestas típicas” and (also slowly disappearing) “rondallas”

(that is, orchestras consisting of violins, mandolins, flute and

piano). By far the most common dance recorded is tango, followed by

vals, some occasional “criollo” or “foreign” dances.

Milongas, however, appear neither as dance nor as vocal music.

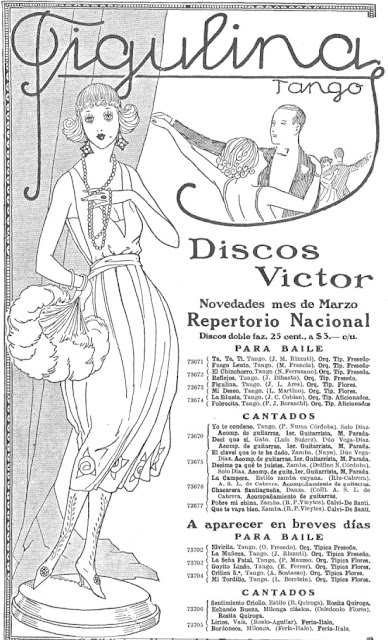

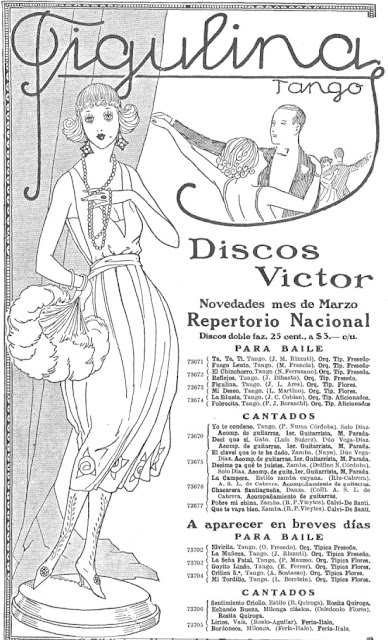

In

the 1920s, one can occasionally find recordings of pieces that are

identified as milongas. They are not dance pieces, however, but

songs, typically with guitar accompaniment. The following example

includes two milongas: one is composed and sung by Rosita Quiroga,

the other is composed and sung by the duo Néstor Feria (“El Gaucho

Cantor”) and Ítalo Goyeche.

|

| Advertisement Discos Victor, Buenos Aires, 1923 |

In

summary, sales advertisements of music records from the first three

decades of the 20th century

demonstrate that tangos were

recorded and sold from the very beginning of music recording in

Argentina. The formation of a standard tango orchestra and a focus on

dance music commenced after 1912, when tango had become popular in

Paris and received world-wide attention. Records with milongas, on

the other hand, were rarely advertised, and these pieces were not

recorded by orchestras but were songs with guitar accompaniment.

3.

The Meaning of “Milonga” and “Milonguero” before 1930

From

its very beginnings, tango was always associated with dance. Most

tangos were composed as instrumental music, to be played by

instrumental ensembles of various sizes. In the early days of tango,

pieces with texts were relatively rare. Yet, if a text was written,

it often broached the topic of dancing tango and dancing it well. In

Villoldo's El Torito, for example, the narrator of the song

prides himself with his skill in dancing the national Argentinian

dances (which, incidentally, do not include the milonga):

Aquí tienen a “El

Torito",

el criollo más

compadrito

que ha pisao la

población.

y en cualquier baile

argentino

donde yo me he

presentao,

pues yo y mi prenda

formamos

la zamacueca, el

cielito,

|

Here he is, “The

Bullock”,

and in every

Argentinian dance

even the best

dancing lad

because I and my

better half make

the zamacueca,

the cielito

the huella

and the pericón.

|

By

contrast, the association between milonga and dance was much more

ambiguous. One can find text sources that recount situations where

one danced to the music of a milonga, but such descriptions remain

very general and do not enter into specifics of the dance. The reason

for this is, in part, that the term “milonga” was not only used

to describe a specific type of music, but it was also used in a very

general sense for events at which music was performed and, more

specifically, the performance of a poem, sung to the accompaniment of

a guitar.

|

| Illustration, “La Milonga del Cocoliche”, Caras y Caretas, Buenos Aires, 1916 |

The

milonga, therefore, had a very strong association with poetry and

the sung performance of a poem. In the late 19th and early

20th centuries, writing poetry was a very popular pastime in Argentina, enjoyed and practiced in all walks of life. The milonga was one of

the popular poetic forms—like the vidalita, relación, décima,

triste, etc.—and it was meant to be sung with or without guitar.

José Betinotti, Milonga Obsequio, 1913

As

poems, milongas are narrative texts, that is, they consist of

multiple verses and relate a story. Depending on the narrator, the

text may describe a scene from country or city life, but many are

sentimental accounts of misery and lost love.

It

follows from the affiliation between milonga and poetry that the

“milonguero”, the practitioner of milongas, was not a dancer (its

modern connotation) but a composer or performer of milongas. In 1920,

for example, the journalist Ricardo Sanchez described the milonguero

as the urban counterpart to the rural itinerant singer, the payador:

The milonguero is well known in the Republics of the River

Plate. His personality has something of the payador, the

gaucho poet (admirably described by Ascasubi). With the exception,

however, that the latter encompasses wider horizons and, improvising

to the cadence of the music, raises his inspiration from the ardent

patriotic song that electrifies, to the moving sentimental triste;

whereas the former cultivates a special genre, eminently marked, with

a suburban flavor that his mates enjoy.

There

is another distinction to be made as well. The payador is an

exclusively rural type; he is the troubadour of our highlands and his

stage are the bodegas and shelters of the countryside. The milonguero

is found only in the cities. The locations in which he performs are

the small cafés of the suburbs, the dance and gaming halls known as

academias, where the most select of lower class fellows get

together.

…

There are only a few legitimate milongueros among us. The

majority of those who call themselves so are no more than routine

imitators, or they sing—lacking that spontaneous inspiration of the

early ones—what they have learned from memory. But the others are

most of the time original and charming.

The

association between milonga and singing continued through the 1920s

and was expressed in tangos as well. The text of Carlos di Sarli's

Milonguero viejo dedicated to Osvaldo Fresedo and written by Enrique Carrera Sotelo, narrates the

nightly serenade of a milonguero:

El barrio duerme y

sueña

al arrullo de un triste

tango llorón;

en el silencio tiembla

la voz milonguera de un

mozo cantor.

La última esperanza

flota en su canción,

en su canción maleva

y en el canto dulce

eleva

toda la dulzura de su humilde amor.

|

The quarter sleeps and dreams

to the lullaby of a sad, weepy tango;

through the silence trembles

the milonguera

voice of a young singer.

The last hope runs

through his song,

through his

beguiling song

and sweet singing he

raises

all the sweetness of

this humble love.

|

Enrique Carrera Sotelo, Milonguero viejo

Even

in 1931, when Homero Manzi and Sebastián Piana composed their

Milonga sentimental and planted the seed for a new kind of

milonga, the protagonist of the poem was a singer:

Milonga pa' recordarte.

Milonga sentimental.

Otros se quejan

llorando

yo canto pa' no llorar.

...

Milonga que hizo tu

ausencia.

Milonga de evocación.

Milonga para que nunca

la canten en tu balcón.

|

Milonga to remember,

sentimental milonga.

others lament weepingly,

I sing so as not to weep.

…

Milonga caused by your absence,

milonga of reminiscence.

Milonga so that they may never

sing it on your balcony.

|

Homero

Manzi: Milonga Sentimental

4.

Tango and Milonga As Musical Forms

The

different purposes of tango and milonga resulted in different musical

structures. Since the music of a milonga was an accompaniment to

poetic text, the music was kept simpler in order not to distract from

the vocal performance of the “milonguero”. Benotti's milonga

Obsequio, given as an example above, begins with a short

guitar introduction of four measures (a). Then, the first strophe of

the milonga is sung, consisting for two phrases of eight and twelve

measures (bc), respectively. The guitar introduction is repeated and

the next strophe is sung, and so forth. The resulting musical form is

a simple repeating scheme of introduction and strophe:

a

bc a bc a …

Tango,

however, was primarily instrumental music, and the musical form

needed to be more elaborate to make it interesting to the listeners.

We mentioned above that the tango “Don Pedro” consisted of three

sections, the third part of which (C) being frequently labeled as a

“Trio”. Such a three-part division is typical for tangos composed

before 1930.

Each

of the three sections has its own melodies, composed in a different

character to distinguish it audibly from the others. In addition, the

sections are harmonically differentiated, and here the “Trio”

section was the one that provided the most striking harmonic “color”

to the piece. The early composers, like Villoldo, liked to move into

the relative major or minor key (depending on the main key of the

piece), later composers were fond of the parallel major or minor key,

respectively.

One

may look upon the sections as building blocks from which a piece is

constructed by means of repetition. A repetition scheme may look like

AB C AB or ABC ABC A, but there is no general rule on how such a

scheme is to be executed. In fact, much of the musical interest stems

from the variety with which tangos can be formally organized.

Re-arranging a repetition scheme was also a means for orchestras to

create a version distinct from other orchestras.

5.

From Tango to Milonga: Villoldo's El Porteñito

El

Porteñito is one of Villoldo's most successful compositions,

having been recorded numerous times in a long series starting before

1906. The record advertisements from 1906 and 1909, given above,

include three versions: two for voice and orchestra—sung by “Mrs.

de Campos” (1906) and Alfredo Gobbi (1909), respectively—and one

orchestra version played by the house orchestra of the Victor company.

As

one of the relatively few tangos that had a text, El

Porteñito was recorded by many singers. The following

example presents a French singer, Andrée Vivianne (or Andhrée

Viviane, as she was known in Paris), who worked for some years in

Buenos Aires and recordedit there in 1909.

El Porteñito, Andrée Vivianne, 1909

If

the habanera rhythm and the tempo of the orchestra introduction hints

at a modern-day milonga, the character of the piece changes once the

singer begins with the first strophe; the tempo is slowed down

considerably. In fact, the rendition is not a dance at all: there are

too many tempo changes, ritenutos, and fermatas for any dancer to

follow. This recording represents a typical concert performance of a

song, as it would be given in a theater, varieté, or cabaret.

Alfredo

Gobbi and his wife Flora Rodríguez recorded a similar version, also

with orchestra accompaniment. However, they changed the text and

turned the tango into another kind of stage performance they

specialized in: a comic scene. El criollo falsificado tells

the story of an immigrant to Buenos Aires who pretends to be a

genuine “criollo” and is proud of his tango skills. His mangled

Spanish and clumsy behavior unmask him, however, as a recently

arrived “peasant gringo”, and he is duly ridiculed by the genuine

“porteña” Flora Rodríguez.

El Criollo Falsificado, Flora Rodríguez and Alfredo

Gobbi, 1906

In

this recording, the orchestral interludes between strophes are

replaced by dialogue. The performance is, therefore, even less of a

dance than the Vivianne recording. However, since the subject matter

of the text touches upon dancing, it is entirely possible that the

Gobbis also danced during the performance—a tango, of course.

The

following version of El Porteñito, recorded in 1949 by Adolfo

Pérez and the Orquesta Típica de la Guardia Vieja, is actually the

youngest one we are going to present. Yet, as the name of the

orchestra and instrumentation (bandoneons, violins, a flute, and 2

guitars instead of a piano, no double bass) suggest, the orchestra

tried to invoke a tango style of earlier times.

El Porteñito, Adolfo Pérez and the Orquesta Típica

de la Guardia Vieja, 1949

Pérez's

recording is an odd interpretation of El Porteñito, inasmuch

as it mixes elements of different phases in the development of tango.

An instrumentation with guitars and flute was characteristic of tango

orchestras around 1915. At that time, melody and the accompaniment

would have been clearly separated, with the guitar playing a clear

and steadfast habanera rhythm. Just as the single flute, the violin

and bandoneon were not always doubled in the orchestra. These

instruments would have played the melody together, only occasionally

adding some embellishments. Pérez's instrumentation is much more

complex than that of early tangos. He introduces lots of counter

melodies, full harmonies, lively bass lines that one would expect

from a symphony orchestra rather than a tango band. In this respect,

Pérez's El Porteñito is a product of the 1940s, but it was

dressed up as a slow tango with a habanera rhythm in order to sound

“historic”.

The

Orquesta Típica Victor's rendition of El Porteñito, instead,

is representative of the style of the late 1920s. Different from the

examples presented above, the dotted habanera rhythm has completely

disappeared from the accompaniment. Instead, a steady pulse of

straight eighth notes provided by the piano and lower bandoneons is

heard almost incessantly throughout the piece. It lends a march-like

character to the recording and makes clear what the music is intended

for: dance, that is, tango.

El Porteñito, Orquesta Típica Victor, 1928

Juan D'Arienzo recorded a number of Villoldo's tangos: some of them

as milongas, others as tangos—including El Porteñito.

Stylistically, his version of does not differ significantly from the

one recorded by Típica Victor nine years earlier. Both orchestras

have dropped the habanera rhythm, play in about the same tempo, and

use the same instrumentation. Differences are mainly a matter of each

orchestra's own style. For example, D'Arienzo has the bandoneons play

a variación in section C and the last repetition of section

A. And, as if to make his version sound even more like a tango, he

changed the rhythmic structure and added more síncopas, most

obviously in section B.

El Porteñito, Orquesta Típica Juan

D'Arienzo, 1937

Our final example of El Porteñito, recorded 1943 by Ángel

d'Agostino, is probably the best known version today.

El Porteñito, Orquesta Típica Ángel

d'Agostino, 1943

The

recording is a very clear example of a “modern” milonga: a dance

piece with a speedy tempo and a well articulated habanera rhythm in

the accompaniment. This milonga is no longer a song, a poem

accompanied by a guitar. The text has been changed and shortened,

just to be sung to two repetitions of the B section. In comparison to

the earlier sung versions of El

Porteñito

presented here, the text has become secondary. The song

has become a milonga as we understand it today: a

piece of dance music.

It

is clear that by the time of d'Agostinos recording, the very concept

a milonga had changed since the late 1920s. This is a history of its

own and beyond the scope of this presentation, but to demonstrate

once more that musicians thought differently about the milonga before

and after the 1930s, we present one more example.

In

the late 1920s, many recordings were released whose titles evoke the

milonga: “Cuando llora la milonga”,

“Milonga”, “Milonga con variación”, “Milonga canyengue”,

“La eterna milonga”, “Milonga criolla” (Canaro, 1928), etc.

All these pieces were, however, tangos. Even Canaro's “Milonga

criolla” of 1928, a tango, is not identical with his well-known

recording of the milonga “Milonga criolla” of 1936. Some thirty

years later, however, he recorded the tango again—this time under

the title “Arrabalera” and turned into a … milonga.

Orquesta Típica Francisco Canaro (1936, 1928),

Quinteto Pirincho (1960)

© 2017 Wolfgang Freis