1. Einleitung

Unser

letzter Artikel beschäftigte sich mit der Frage, wie Tonalität mit

Hilfe von Tonleitern (Tonartschlüssel) und harmonischen

Progressionen von der Dominante zur Tonika (in den folgenden

Beispielen als V, beziehungsweise I angezeigt) ausgedrückt wird.

(Siehe Eine kurze Tangoharmonielehre, Teil I

für eine Erörterung der Bewertung von Tonarten.) Hier werden wir zwei weitere Begriffe der Dur- und

Moll-Tonalität behandeln: die Subdominante sowie die Zwischen- oder

Nebendominanten.

1a. Die Subdominante

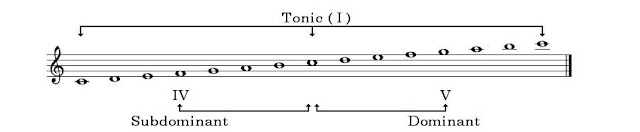

Die

Subdominante leitet ihren Namen von ihrem Verhältnis zur Tonika ab.

Während die Dominante sich eine Quinte (d.h. fünf Tonleiterstufen)

über dem Grundton befindet, liegt die Subdominante eine Quinte unter

dem Grundton. Durch Umkehrung ist sie auch wieder auf der vierten

Stufe über dem Grundton zu anzutreffen. Sie wird daher üblicherweise

durch die römischen Ziffern IV angezeigt.

Die

Subdominante ist ein gewöhnlicher Bestandteil von Kadenzen, in denen

sie oft vor der Dominante anzutreffen ist. Eine Progression von der

Tonika zur Subdominante, dann zur Dominante und schließlich wieder

zur Tonika ist typisch als Kadenzformel (I-IV-V-I, siehe das folgende

Beispiel).

Darüber

hinaus findet man die Subdominante im sogenannten Plagalschluss (auch

Plagalkadenz), der als Subdominant-Tonika-Progression an eine normale

Kadenz angehängt wird ( … V-I-IV-I). Diese Figur ist oft am

Schluss von Kirchenliedern zu finden.

Beispiel

2: Kadenzen mit Subdominanten

1b. Nebendominanten

Das

Konzept einer Nebendominante ist einfach: man richtet einen Akkord so

ein, dass er als Dominante für einen anderen Akkord fungiert, der

nicht die Tonika ist. Um zu einer Nebendominante zu werden, muss

zumindest ein Ton des Akkordes verändert werden. Der daraus

resultierende Dominant-Akkord gehört nicht zu den natürlichen

Zusammenklängen der Tonart, in der er verwendet wird. Er ist

sozusagen eine Dominante, die (vorübergehend) von einer anderen

Tonart ausgeborgt wird.

Nebendominanten

werden dazu verwendet, die Harmonien eines Stückes zu bereichern und

die Spannung vor der Auflösung zur Tonika zu steigern. Dies wird

häufig dadurch erreicht, dass der Dominante eine Nebendominante

vorgesetzt wird (im folgenden Beispiel als V/V angezeigt). Die

Nebendominante löst sich in der Dominante auf, die dann wiederum

ihre Auflösung in der Tonika findet.

Als

Beispiel für eine einfache harmonische Progression in Dur folgt eine

kurze Kadenz, die mit Dominante und Tonika endet:

Beispiel

3: einfache Kadenz (zur Vereinfachung sind nur Dominante und

Tonika angegeben)

Um

die Empfindung von Spannung und Auflösung zu erhöhen, kann die

Dominante von ihrer eigenen Dominante (angezeigt als V/V in folgenden

Beispiel) eingeführt werden. Der Klavierauszug zeigt, dass der

Akkord nicht in seiner natürlichen Form gesetzt wurde, sondern das

ein Ton (der tiefste) um einen Halbton erhöht wurde. Diese Erhöhung

erzeugt einen Leitton, d.h., die durch die Erhöhung erzeugte

Spannung bedingt eine Auflösung in dem darauffolgenden Ton.

Beispiel

4: Kadenz mit Nebendominante

Es

wurde obern erwähnt, dass eine Nebendominante auf jedem Akkord

gebildet werden kann. Selbst Nebendominanten können das Zielobjekt

einer weiteren Nebendominante werden, wie das nächste Beispiel

zeigt. Vom zweiten bis zum vierten Takt folgen vier Dur-Akkorde

aufeinander. Jeder von diesen bildet eine Dominante zum

darauffolgenden Akkord. So bildet sich die folgende Progression:

H-Dur – E-Dur – A-Dur (Dominante) – D-Dur (Tonika).

Beispiel

5: Kadenz mit zwei Nebendominanten

2. “El Himno Bonaerense”

Angel

Villoldos El Porteñito

gehört zu den bekanntesten Tangos. Schon bald nach seiner

Komposition im Jahre 1903 war er einer der ersten, die auf

Schallplatte aufgenommen wurde. Villoldo bezeichnete das Stück als

tango criollo, aber

seit der zweiten Hälfte der 30er Jahre wird er auch als Milonga aufgeführt. So gut wie alle argentinische Filme, die in Buenos

Aires um die Wende des 20th

Jahrhunderts spielen, weisen eine Tanzszene auf, in der El

Porteñito—oft in

halsbrecherischem Tempo—gespielt wird. Wenn es einen Tango gibt,

der mehr als jeder andere Buenos Aires repräsentiert, dann ist es

sicherlich El Porteñito.

3. Die formale Struktur

El

Porteñitos

formale Struktur ist einfach und sehr symmetrisch. Sie besteht aus

drei Teilen mit einer Länge von 16 Takten (im Folgenden als A, B

beziehungsweise C angezeigt). Die drei Teile sind „durchkomponiert“,

d.h., sie wurden durchgehend ohne Angabe von Wiederholungen notiert.

Dessen ungeachtet endet jeder Teil mit einer klaren und starken

Kadenz, die einen Einschnitt in den Ablauf der Musik bewirkt und

damit den Wechsel von einem Teil zu anderen anzeigt.

Die

Teile ihrerseits teilen sich in zwei acht-taktige Phrasen auf (im

Folgenden A1, A2, B1, usw.). Diese Vorder- und Nachsätze sind sich

melodisch und harmonisch sehr ähnlich und unterscheiden sich nur im

Abschluss. Teil A zeichnet sich durch lebhafte Motive mit kurzen

Notenwerten in absteigender Bewegung aus, die zu kleinen Figuren im

typischsten Tangorhythmus führen, der síncopa

(im folgenden Beispiel durch eckige Klammern über dem Notensystem

angezeigt).

|

Beispiel

6: Teil A1, Vordersatz

|

|

Beispiel

7: Teil A2, Nachsatz

|

Beispiel

8: Teil A

Auch

die Vorder- und Nachsätze des B-Teils ähneln sich. Um Gegensatz zu

A ist die melodische Bewegung durch längere Notenwerte allerdings

ruhiger, und die síncopa wird fast vollkommen vermieden.

Beispiel

9: Teil B1, Vordersatz

|

Beispiel

10: Teil B2, Nachsatz

|

Beispiel

11: Teil B

Es

muss angemerkt werden, dass die fundamentale Struktur der Melodien in

den Teilen A und B sich nur gering voneinander unterscheiden. Die

Richtung der melodischen Bewegung ist die gleiche (abwärts), und die

Zielnoten der absteigenden Motive decken sich. Ein Vergleich des

melodischen Grundrisses der Teile A und B veranschaulicht die

Gemeinsamkeiten der beiden Teile.

|

Beispiel 12:

Teile A und B, melodischer Grundriss

|

Im

Gegensatz dazu zeigt sich im Teil C eine größtenteils aufsteigende

Bewegung der Melodie ohne síncopas.

|

Beispiel

13: Teil C1, Vordersatz

|

|

Beispiel

14: Teil C2, Nachsatz

|

Beispiel

15: Teil C

Der

melodische Grundriss bestätigt die aufsteigende Tendenz der Melodie

und damit den Kontrast zu den Teilen A und B.

|

Beispiel

17: Teil A1, Vordersatz

|

|

| Beispiel 18: Teil B1, Vordersatz |

Beschreiben

wir diese Progression rückschreitend in ihrer funktionalen

Bedeutung, so können wir feststellen, dass der Tonika (I) die

Dominante (V) vorangeht, dieser die Dominante der Dominante (E) und

dieser noch einmal eine weitere Dominante (H) vorgesetzt ist.

Die

Harmonien in C1 verbleiben dagegen innerhalb der Grenzen von Tonika

und Dominante. Nur am Ende schwingt der harmonische Impuls mit dem

Plagalschluss in die entgegengesetzte Richtung zur Subdominante.

|

Beispiel

19: Teil C1, Vordersatz

|

Betrachtet

man den größeren Zusammenhang, in dem dieser einmalige

Plagalschluss erscheint, so fällt auf, dass er nicht zufällig oder

willkürlich eingesetzt wurde. Teil C entspricht einem „Trio“,

einem Abschnitt, der in instrumentalen Tangos so komponiert wurde,

dass er sich stilistisch von den anderen Teilen unterschied. Wir

haben bereits festgestellt, dass sich Teil C von den anderen beiden

Teilen in der Richtung der melodischen Bewegung abhebt. In A und B

verläuft diese Bewegung abwärts, in C aber aufwärts. Entsprechend

macht sich auch ein Unterschied in der harmonischen Richtung

bemerkbar: A und B bewegen sich im Raum der Dominante und ihrer

Nebendominanten, während C in der Subdominant-Tonart steht und in

der Mitte einen Plagalschluss aufweist. Die harmonische Bewegung in

Teil C entfaltet sich damit in der entgegengesetzten Richtung von A

und B.

5. Die Wiederholungen

Wir

haben anfangs erwähnt, dass El Porteñito “durchkomponiert”

wurde, d.h., Teile A bis C wurden ohne Angaben von Wiederholungen in

der Partitur niedergeschrieben. Allerdings werden Kompositionen

dieser Art immer auf eine oder andere Weise mit Wiederholungen

gespielt. Ein einfaches, normales Wiederholungsschema besteht darin,

die Teile A bis C durchzuspielen und dann A und B zu wiederholen.

Damit wird die kontrastierende Anlage von C betont und dem ganzen

Stück eine symmetrische Struktur verliehen (ABCAB). Das Quarteto

Roberto Firpo hat dieses Schema in einer Aufnahme aufgegriffen und

durch eine zusätzliche Wiederholung aller drei Teile erweitert (AB C

AB C AB).

Beispiel 20: El Porteñito, Quarteto Roberto Firpo (1936)

Man

trifft das Standardschema oder eine Variation davon oft in den vielen

Aufnahmen El Porteñitos an. Tango-Orchester verstanden sich

allerdings darauf, ihre eigenen, bezeichnenden Arrangements aufzunehmen. Zwei interessante Versionen von Villoldos Tango mit

abweichenden Wiederholungsschemen sollen hier erwähnt werden.

Die

erste ist Aufnahme mit dem Orquesta Típica Victor aus dem Jahre

1928. (Wir möchten dazu auffordern, dem hervorragenden ersten Geiger

dieser Aufnahme besondere Aufmerksamkeit zu schenken. Leider ist uns

sein Name nicht bekannt, aber es handelt sich wahrscheinlich um

Elvino Vadaro oder Agesilao Ferrazano, die im Típica Victor zu Ende

der 20er Jahre mitwirkten.)

Beispiel 21: El Porteñito, Orquesta Típica Victor

Auffallend

an dieser Version ist, dass sie mit Teil C, also in der

Subdominant-Tonart, beginnt. Das ganze Wiederholungsschema ergibt

sich wie folgt: CABCA.

Francisco

Canaro hat El Porteñito mindestens dreimal eingespielt. Zwei

dieser Aufnahmen folgten dem Standardschema in den Wiederholungen,

aber eine Aufnahme mit dem Quinteto Pirincho aus den 50er Jahren

weicht entschieden davon ab.

Beispiel 22: El Porteñito, Quinteto Pirincho

Canaro

wiederholt in dieser Version alle drei Teile der Reihe nach. Damit

beginnt das Stück in D-Dur, endet aber in G-Dur, der

Subdominant-Tonart.

Die

Versionen von Canaro und der Típica Victor werfen die Frage auf, ob

die Umgestaltung der drei Teile den formalen und tonalen Zusammenhang

des Stückes verändern. Die Wiederholungen im Standardschema folgen

der kompositionstechnischen Logik: Teile A und B artikulieren eine

musikalische Idee (D-Dur), Teil C präsentiert ein Gegenstück

(G-Dur) und die Wiederholung von A und B kommt auf die Anfangsidee

zurück. Formal und tonal ist der Unterschied zwischen AB und C

offensichtlich: das Stück endet dort, wo es begann und stellt eine

geschlossene Einheit dar.

Die

Victor und Canaro Versionen lösen den formalen und tonalen

Zusammenhang auf. Aber diese Orchester standen damit nicht allein da.

Es war keineswegs ungewöhnlich, ein Stück mit einer „falschen“

Tonart anzufangen oder zu beenden. Stücke wie El Porteñito

waren dem Publikum bekannt genug, um schnell als besonderes

Arrangement erkannt zu werden. Der Zweck heiligte offensichtlich die

Mittel.

© 2017 Wolfgang Freis