( Deutsche Version )

In the 19th century, Paris was the music capital of the Western world. To make a career in Paris was the dream of every ambitious musician, and what happened in Paris was taken note of everywhere. Sebastián Iradier was one of many Spanish composers who established professional ties to Paris. Being named professor of singing by the empress Eugenia made him also one of the more successful musicians in Paris.

Cuba being a Spanish colony at the time, it is not surprising that Spanish composers adopted Cuban music elements they perceived as part of their national (colonial) heritage. However, the habanera gained also popularity in other countries, which had neither colonial or language connections to Cuba. The success of the habanera in Paris, therefore, is best explained by an interest in the exotic.

Throughout the 19th century, artists and their public were fascinated by different and unfamiliar cultures. In music, it made itself evident, for example, in a host of operas playing in far away places (Lakmé, The Perlfishers, Aida, etc.) and orchestra and piano works based on dances perceived as “exotic” by their producers and audience. These were described as Slavic, Hungarian, Cuban, or from yet another place.

1. Le Petit Coco d'Amérique

The French singer Louis Bousquet published in 1858 in Paris a piano score of a chanson havanaise, or tango, entitled Le Petit Coco d'Amérique. The text of the song tells the story of Coco, a black man originally from Mozambique who had come from South America to Paris as a pauper in order to make his fortune. He has succeeded and became rich by singing and dancing the tango in public. Dressed like a gentleman, Coco plans to return to South America and buy his father and his beloved out of slavery.

Bousquet performed Le Petit Coco d'Amériqueat the Théâtre de l'Ambigu-Comique as an entr'acte during the performance of a dramatic play “à grand spectacle”: Les Fugitifs by Auguste Anicet-Bourgeois and Ferdinand Dugué. The play takes place in India and includes characters like French settlers, English soldiers and sailors, as well as native servants, rebels, and bandits. Bousquet's number had nothing to do with the play, other than the element of exoticism: Coco from Mozambique dancing tango in the streets of Paris is no less exotic than the rescue drama playing in India.

The musical structure of Le Petit Coco d'Amérique is not very interesting with respect to our discussion. It is a simple strophic song consisting of two phrases with a short introduction and a coda. The habanera rhythm provides the rhythmic foundation of the piece, but there are neither melodic cross rhythms nor síncopas. The melody always moves with the habanera rhythm, never against it.

One encounters this kind of tangos—a simple strophic song with accompanying habanera rhythm—intermittently in the Spanish zarzuela. And, in fact, this is where Bousquet's song originated. The same music appears in the zarzuela El Relámpago, composed by Francisco Asenjo Barbieri in 1857, just one year before the publication of Bousquet's song. In the zarzuela, this piece, which is called a tango, represents finale of the work with the title “¡Ay, qué guto, qué placé!” (Recordings are available on Youtube.)

On the cover page of the piano score Bousquet is credited as the creator of Le Petit Coco d'Amérique, but he is at best the author of the French lyrics. One should not dismiss Bousquet's publication as just as a case of music plagiarism, though, as it is also a record of the role that he created and performed on stage.

Barbieri's zarzuela plays in colonial Cuba. The tango is sung and danced by the “coro de negros” who are the servants to the white main characters. Corresponding to many habanera songs, the characters of¡Ay, qué guto, qué placé!(¡Ay, qué gusto, qué placer! in standard Spanish) sing in the supposed dialect of Cuba's black people about the pleasures of dancing. Bousquet's stage character, Le Petit Coco d'Amérique, follows the model of Barbieri's tango. Coco is black, sings in incorrect French, and has made his fortune by singing and dancing tango.

We don't know why Bousquet chose to pilfer Barbieri's tango and masquerade as a singing and dancing black man. His choice allows one or two important deductions, however. First, the association oftango, dance, and black people—which, as we have seen, was prevalent in the habanera-like pieces of Spanish composer—was self-evident to Bousquet. Second, this association probably originated on European stages and was disseminated through public performances like Barbieri's zarzuela and Bousquets entr'acte.

2. Zig-zig-zig-tong

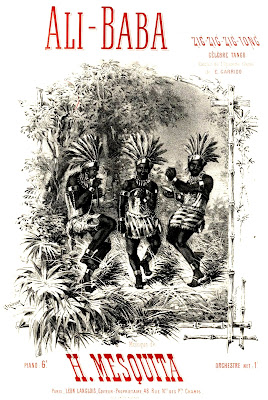

Henrique Alves de Mesquita (1830-1906) studied music at the conservatory of Rio de Janeiro and, upon graduation, was awarded a scholarship to continue his studies in Paris. His first published compositions appeared in the late 1850s (piano dance music, mostly quadrilles and polkas). After leaving Paris, he established himself as a composer, orchestra director, and professor of music in Rio de Janeiro and made a name for himself as a composer of operettas. One of his pieces that is still performed today is a tango from his operetta Ali Baba (with a text by the Portuguese librettist Eduardo Garrido, based on the story from One Thousand and One Nights). (Recordings of the piece are available on Youtube.)

This tango, entitled Zig-zig-zig-tong, is not unlike the tango of Barbieri's El Relámpago. It is a short piece of two sections that show the typical phrase divisions of simple song and dance pieces (32 + 3 measures in the first section, 16 + 5 in the second).Both sections are tonally contrasted by means of a pattern common in habanera-like pieces, that is, by parallel keys (a minor and A major, respectively).

The habanera rhythm provides the rhythmic foundation in the bass accompaniment through the entire piece. There are no melodic cross rhythms but the síncopais a prominent rhythmic figure in the first section.

By contrast, the second section introduces an energetic, polka-like rhythm into melody. This, together with the key of A major and a faster tempo, lends the section a lively dance-like character.

Today, the piece is commonly known as “the tango from Ali Baba”. However, the fact that it actually has a title, Zig-zig-zig-tong, is an indication that it may have had a text and was a song-and-dance number in the operetta, just as Barbieri's "¡Ay, qué guto, qué placé!". The cover illustration of the piano score suggests as much: it shows three black men dancing and making music, thus associating tango again with black people and dance.

The tango Zig-zig-zig-tong exhibits many of the typical elements that characterize habanera or habanera-like compositions. Alves de Mesquita went to Paris at a time when the habanera was becoming a musical genre popular with composers in Spain and France. Whether or not he became acquainted with the habanera then and took it back Rio de Janeiro seems unlikely and, in the end, is not very significant. More important is that he kept composing music, including tangos, after his return that appealed to the audience and publishers in Paris. This demonstrates that a continuous bilateral cultural exchange was maintained by professionals (composers, performers) and professional institutions (theaters, publishers) across continental boundaries.

An interesting side note to our discussion: Alves de Mesquita is also credited with being the originator of a Brazilian music style, the maxixe (also known as “Brazilian tango”), which conquered the dance floors in Europe and North America just a few years before Argentinian tango became all the rage in 1912.

3. El Negro Schicoba

A perusal of Argentinian writings on the history of tango sometimes leaves the impression that the country was something of a musical backwater even during the second half of the 19th century. The reason for this is that by trying to trace the Argentinian roots of tango, researchers focussed on that which could be claimed as “Argentinian” and rejected everything else.

If one looks at musical life in Buenos Aires as a whole, however, one notices that it was not that different from Paris or Madrid. People played and danced to the same kind of music and enjoyed performances from numerous foreign artists in theaters, concert halls, and cafes. In December 1862, the newspaper El Nacional reported on a performance of the actor Fernando Cuello:

Cuello caused a sensation in this show [of the comedy Fuego en el Cielo]. What elated the audience the most was a tangohe sang at the end. It received an ovation as only few pieces have. As a proof that it was justified, we are offering [Cuello] a newtangoso that he may have it set to music and sing it.

The name and music of the piece are unfortunately unknown, nor do we know what role the singer impersonated when he was performing his tango. The situation in which the piece was performed—a singer's or dancer's showpiece given in addition or as an entr'acte tothe scheduled program—recalls Bousquet's performance of Le Petit Coco d'Amérique in Paris.

A similar piece was performed in 1867 at the Teatro Argentino in Buenos Aires. At the end of a performance of a comedy, the first North-American actor working in Argentina, Germán (Herman?) MacKay, sang El Negro Schicoba. The actor wrote the text himself but the music, which has survived as a piano score, was composed by an Argentinian, José María Palazuelos. MacKay, who actually was an actor of serious roles, in this occasion dressed up as a black broom vendor and sang, presenting a farcical dancing routine and improvising risqué verses to the thunderous applause of the audience.

The piano score does not indicate what kind of piece it is, but it is obviously a habanera-type composition. Like the two tangos discussed above, the piece is a simple two-part song consisting of two phrases of 16 and 14 measures, respectively, plus and introduction and a coda. The accompaniment is based on a continuous habanera rhythm.

The melody of the first section makes use of the síncopa. Harmonically, the antecedent phrase introduces the main key, e minor, whereas the consequent phrase shifts to the relative key, G major. The second section employs the typical habanera figure with triplets. Here they are not set in a cross-rhythmic pattern against the dotted habanera rhythm, however. The accompaniment switches to triplets as well and the rhythms in both voices are synchronized. Harmonically, the antecedent phrase moves to the parallel key E major and returns to e minor in the subsequent phrase.

El Negro Schicoba, interestingly, appears to be a recapitulation of the pieces discussed earlier. As other habanera-like pieces, it has a black character who sings and dances. The setting in which the performance took place is equivalent to the presentation of Le Petit Coco d'Amérique. As a musical composition, the piece corresponds formally to ¡Ay, qué guto, qué placé! and Zig-zig-zig-tong. Harmonically, it exploits parallel and relative keys just like La Flor de Santander did.

Looking at all the pieces discussed in our study as a collection, it emerges that, on the one hand, it is impossible to attribute definitive characteristics to any of the habanera-like compositions. Whether habanera, canción americana, or tango, all categories share stylistic and formal traits, but these traits are neither limited to a particular category nor are they necessarily present. The names of the categories are designations, and as such they are imprecise to the point of being useless for analytical purposes.

Nevertheless, as a family of music forms, habanera-like pieces show consistent, reoccurring traits: the habanera rhythm as a continuous accompaniment figure, cross-rhythms, síncopas, tonal contrasts between parallel and relative keys, a connection to dance, and—if sung—a textual association with black people. Rather than taking compositions of the kind and period under consideration as distinct types, it seems more appropriate to look at them as members of one category, that is, as examples of the habanera.

The habanera emerged as a musical form in the 1850s in Spain and was quickly taken up by composers outside Spain. The pieces we have scrutinized so far can be dated roughly within the timespan of two decades. Significant is the geographical distribution in which the pieces were written and performed, reaching from Madrid, to Paris, Rio de Janeiro, and Buenos Aires. The recurrence of common stylistic traits and similarities in performance settings suggests that there existed conventions for composing and performing a habanera that were universally understood and appreciated. It means that a habanera or tango written in 1870 in Paris would have been appreciated as a tango in Buenos Aires and vice versa. Furthermore, it would have been self-evident to the audience in either city that an actor singing and dancing a tango would dress up a as black person because of its notorious Cuban association.

Finally, one should take note that the dissemination of the habanera did not occur by chance but ran through network channels of professional musicians. Composers took their inspiration from Cuban music, but performers and music publishers carried their works to audiences wherever they could find one, be it Madrid, Paris, Rio de Janeiro, or Buenos Aires.

|

| Cover page of a piano score of Francisco Barbieri's El Relámpago, including the tango "¡Ay, qué guto, qué placé!", published 1867 in Montevideo, Uruguay |

© 2019 Wolfgang Freis

No comments:

Post a Comment