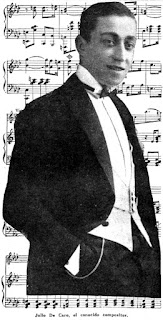

The Kings of Tango: with Julio De Caro,

the popular composer of “Buen amigo”, “Todo corazon”, and “Guardia vieja” [An interview conducted by Ernesto E. de la Fuente, Buenos Aires, 1928]

Julio De Caro

is one of the youngest composers of Buenos Aires. What is more, his

particular appearance makes him seem even younger than he is.

Optimism issues from his demeanor, and his words can not conceal the

satisfaction that saturates his spirit in view of the artistic

perspectives unfolding in his future.

—Porteño,

good friend De Caro?

—With

pedigree. I was born at the corner of Catamarca and Méjico, where I

also spent the years of my childhood and carried out unforgettable

pranks in the company of other neighborhood kids.

—Unforgettable

pranks?

—Good

heavens, they were indeed. The glass panes of the street lights and

the door-to-door salesmen, which were our preferred victims, could

tell you about it.

—You were not

inclined toward music, then?

—Exactly. My

father was a musician and did not wish that I would become one, too.

Therefore, and much to my regret , I went through the grades of

primary school in order to enter, later, the Colegio Nacional Mariano

Moreno.

—What was

your goal?

—To be a

doctor, but a good one. In spite of my artistic success, I still

believe that I could have become a physician capable of being

recognized and making an impression.

—But...

—There are

things in life that can not be foreseen, since they appear to have

been arranged by destiny.

—As with your

beginnings in music?

—I owe them

to my father. In the hours when I was free from school work I learned

solfege and violin—out of obligation more than preference—but by

dint of force, it seems I made good progress, as my family and other

people that came to our house asserted.

—And your

first success?

—It was a

coincidence, since I had never played in public before and never

considered doing so. Neither did I apply myself to musical

composition until, all of a sudden, something awoke in me that could

be called the musical instinct. I was a sleeper, so to speak.

—When did you

have your debut?

—I was hardly

15 years old. One afternoon, a friend and I decided to go downtown to

a dance that was going to take place. The orchestra of my good friend

Firpo, that performed with enviable success, used to be there.

—And?

—During one

of the intermissions, some of my friends asked me to go to the

orchestra stand and play a piece. I did it not without some

discomfort, but since I was already put in a trance to confront the

situation I tried to accomplish it as best I could.

—A success?

—Complete. I

was much applauded, and one moment later my good friend Arolas called

on me to offer me the position of first violin in his orchestra. I

did not accept. First of all I wanted to continue my studies. He

asked me to play with him for only one month, and with the consent of

my father I did so.

—And you

abandoned your studies?

—It was

inevitable. My unexpected triumphs pleased me and I could not give up

the musical career anymore.

—And your

first tango composition?

—I conceived

it while I was working in the Arolas ensemble, one night when we were

performing at a cabaret in the center. It was “Mala pinta”, a

tango that later attained a really considerable success and which

encouraged me to proceed in my career as a composer.

—Which other

successful works do you remember?

—It would be

impossible for me to remember the names of all my tangos. There are

perhaps more than a hundred. But “Buen amigo”, “Tu promesa”,

“Mala Junta”, “El Malevo”, “Copacabana”, “Tiny”,

“Todo corazón”, “Guardia Vieja”, among others, were widely

recognized.

—With

practical and positive results?

—With success

in every sense, even more since I started to make recordings with my

orchestra, which I set up together with my brothers Francisco and

Emilio and the friends Maffia, Laurenz, Blasco and Sciarreta.

—And your

plans for the future?

—There are

many, but I think I must make a trip to Europe very soon, where we

will have the opportunity to work intensely. I have already received

some extremely favorable offers that I would regret not to accept.

—Also dressed

up as gauchos?

—Disguised as

gauchos, you mean. Believe me, it pains me to think that it is

necessary to have recourse to such means in order to excite the

audience in Europe.

—Now that

your career is definitely on track, do you have any particular

ambition?

—To go to New

York, to the joyful people of Broadway, and show them that tango is

beautiful, that they do not understand it, and then—playing it in

its various styles—make them understand it well: right in the

middle of that world of joy, profusion, excitement, and life.

—Which are

the strongest satisfactions that your musical career has bestowed

you?

—The sympathy

that the Argentinian public is showing me, the smiles with which the

people of Buenos Aires greet me. There are many among them who praise

me and whose words and charm make me immensely happy. However, one

great satisfaction that will allow me to take another big step in my

career remains to be fulfilled.

—What is it?

—An

invitation by the Prince of Wales to come to London in order to

promote the “genuine Argentinian tango” there.

—Did he have

the opportunity to become acquainted with it?

—I performed

with my orchestra at one of the private parties given in his honor

when he was in Buenos Aires. One tango, which he had requested, had

to be repeated seven times. And after the wish of the prestigious

visitor had been granted, he said to me:

—“You must

go to London.”

—“I shall

go, your Highness” I answered. And I expect that within the next

eight months I will be performing in the British capital. Upon his

request, I sent the Prince of Wales a series of records with

Argentinian tangos, and I treasure the letter in which he thanked me

for the gift as one of my most precious souvenirs.

—So, De Caro,

are you a happy man?

—To date, I

can state that I am. But I will be much more so the day of my debut

in the capital of the great empire, when I see the successor to the

crown attending my concert; and that day, too, when I shall succeed

in imposing the tango criollo in the midst of the bustle and

feverish joyfulness of the Broadway nights.

Remarks

De Caro's Debut

In his autobiography, published in 1964, De Caro offered a slightly different account of his debut as a tango musician. According to this later version, he was close to 18 years old and played "La cumparsita" with the Firpo orchestra at the “Palais de Glace”. Since “La cumparsita” was composed and premiered during the carnival season of 1917, De Caro must have been at least 17 years old (his 18th birthday falling on December 11, 1917), and not 15 as stated in the interview.

Furthermore, according to

his autobiography, he started to play in Arola's orchestra secretly,

without the consent of his father. When his father demanded that De Caro quit the orchestra and he refused, he was shown the door and for many years had no further contact

with his father.

Tango “Buen amigo”

Julio De Caro dedicated his tango “Buen amigo” to a distinguished Argentinian physician, Enrique Finochietto, who had saved the lives of a friend's wife and child. Finochietto was also a tango enthusiast and admirer of De Caro. He was a regular visitor of De Caro's performances at the “Chanteclair” cabaret in the mid-1920s. De Caro composed a tango, dedicated it to Finochietto, and named it "Buen amigo" in the latter's honour.

The Prince of Wales

Edward III, the Prince of Wales, visited Buenos Aires in 1925. A gala dance in his honor was given at the cabaret “Ciro's”, where which the Julio De Caro orchestra provided the musical entertainment. In the course of the evening, Edward also entered the dance floor during a performance of the tango “Buen amigo”. Shortly thereafter, De Caro was privately introduced to Edward in the office of the cabaret's director. Edward expressed his admiration for De Caro's music and the tango “Buen amigo”, in particular. At a later date, De Caro paid his respects to Edward by sending recordings of his orchestra (which included “Buen amigo”) and, at the occasion of Edwards's marriage, dedicated his tango “Dulce Hogar” to the then Duke of Windsor.

©2017 Translation and Commentary Wolfgang Freis.

No comments:

Post a Comment