In his autobiography,

Julio De Caro reported the discovery of an ingenious bandoneonist. In 1925, Luis Petrucelli wanted to leave the orchestra, and De Caro needed a

player to replace him. By chance, he heard a young musician who

impressed him so much that he offered him the job at once.

|

| Luis Petrucelli |

His decision was not

unproblematic. The musician who had to be replaced was no black horse but a well-known and

accomplished bandoneonist. It was a difficult task for a young

musician with little experience to take the place of an experience

professional.

What is more, one of the

most distinguished instrumentalists played the first bandoneon in De

Caro's orchestra: Pedro Maffia. It comes as no surprise that Maffia

was concerned about De Caro's decision to hire an unexperienced

bandoneonist. His own reputation depended on the quality of the

orchestra with which he performed. For the young musician, it was no

different. To sit next to the great Maffia meant to raise the bas

higher than it was already. (Years later in an interview, he admitted

not to have closed an eye the night before his first performance with

the orchestra.)

It bespeaks the care and

foresight with which the De Caro brothers attended to the young

bandoneonist by introducing him to the orchestra only after they were

sure that he was ready for the task. In an orchestra, it cannot be

taken for granted that a new colleague—especially a young one—is

welcomed with open arms. De Caros remark that, at their first

encounter, Maffia barely greeted the neophyte and that the bassist

Leopoldo Thompson for a start scrutinized him head to toe speaks

volumes about the customs among musicians. To enter an established

orchestra as a young and quite unexperienced musician is a

challenging task—even more so if one has to hold one's ground next

to an outstanding performer of the instrument. Obviously, Julio De

Caro recognized the talent of the young musician. The fact that he

and his brother carefully prepared him for his new assignment shows

also that they knew the mentality of musicians very well and had

enough experience to foster and preserve the new talent.

|

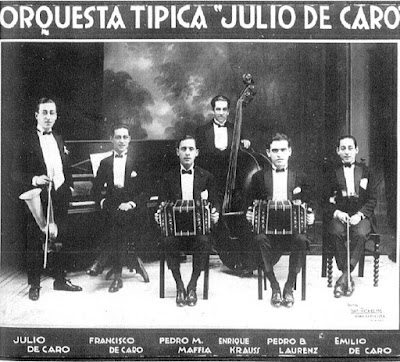

The bassist Leopoldo Thompson (standing left) with the orchestra Francisco

Canaro, 1916

|

( From: Julio De Caro, El Tango en mis Recuerdos)

It was shortly before the

Vogue's Club was closing until the season of the following year

(1925), when Luis Petrucelli informed me that he would leave for Mar

del Plata in order to combine work and summer vacation with his

fiancée. I tried to dissuade him from doing so, but when he promised

to rejoin the orchestra upon his return, I agreed, adding: “The

bandoneon that is going to replace you will be the creditor of your

seat. Well, let us be friends and we will see what the future

brings.” Straightaway I focussed on the search for a new

bandoneonist and tried to find out where I could find Enrique Pollet,

from whom I had received the best professional references as an

instrumentalist.

I was told that he

performed with the orchestra of Roberto Goyneche in a café in Villa

del Parque, and it was said that the group was going to dissolve

soon. I went there to take a look at the bandoneons. Pollet played

very well but the second bandoneonist, whom I did not know, was by no

means inferior to him and had, in addition, a good sense for

interpretation.

At the end of the set, I

decided to hire him instead of Pollet. I asked him his name and if he

knew who I was. “My name is Pedro Blanco and I have known you,

Julio, for many years. I was a young kid then and listened to the

orchestra of you and your partners Minotto and Eustaquio [Laurenz] in

Montevideo. You do remember the Laurenz brothers!? They are my

stepbrothers.”

|

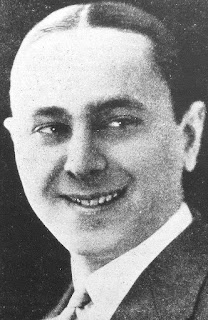

Pedro

Blanco Acosta, „Pedro B. Laurenz“

|

“Yes, I can place you

exactly. Now more than ever, and since you are leaving this

orchestra, I would like to propose that you replace Luis Petrucelli

and play together with the great Pedro Maffia. And, in order not to

break with the tradition of your family name, I have already renamed

you professionally: Pedro B. Laurenz.”

“This offer would be the

greatest thing for me, since I am finishing here tonight. But I do

not think that I am up to the task because I have been playing

publicly only for a short time. To play in your orchestra and replace

Petrucelli, Maestro, is not easy.”

I tried to build his

confidence: “Let me take care of your concerns. The only thing I

ask from you is that before your debut, you rehearse seriously with

my brother Francesco and me in private. Well then, I expect you

tomorrow with your bandoneon at my brother's. Good luck and listen

well to me. Agreed?”

As Petrucelli was not to

leave before his replacement—already found in the person of

Laurenz—was ready, the latter dedicated himself completely to

practicing in order to announce his joining the orchestra as soon as

he was in best condition and equal to the others.

Even though this was not

news anymore and known by all members of the orchestra, Maffia asked

me inquisitively who he was. “He is a great fellow,” I responded.

“And even though he is new, I am sure you will like him!” He was

very concerned, and it almost seemed to be an insult to his

professional reputation that someone in his position would have to

share his responsibility with an unknown. Thus the situation … but

fate had bestowed a Pedro Laurenz on me. If I mention this, in

particular, it is only because my discovery had a special artistic

significance to my ensemble.

At the first session,

Maffia—I remember it well—hardly deigned to greet Laurenz, and

[Leopoldo] “el negro” Thompson examined him head to toe.

Meanwhile Francisco, who knew what class he had, was smiling,

imagining what would happen when this great learner opened his “pot”.

The programmed tangos

were: “Todo corazón”, “Triste”, Cobián's “Los dopados“

(today “Los mareados“), Delfino's “Agua bendita”, etc. As

Laurenz played the first measures, Maffia—who was watching him from

the corner of his eye—could not hide his admiration. And what could

one say as this novice really got started, attacked the arpeggios,

and stuck to the first voice like a shadow. When we had finished,

Maffia besieged me with overwhelming joy, wanting to know where I had

found this “genius”. Like that, Laurenz, on his own account, had

earned with one leap a position that is attained by only a few.

Laurenz played in De Caro's orchestra until 1932. Maffia wanted to start his own ensemble and left the orchestra in 1926. He was replaced Armando Blasco who, together with Laurenz, made up a “much talked-about duo” (De Caro). The De Caro orchestra broke up in 1932. De Caro than formed a larger ensemble with four bandoneons rather than two. The players were: Carlos and Romualdo Marcucci, Gabriel Clausi, and Félix Lispisker. Carlos Marcucci played the lead bandoneon. He also performed as a concert soloist and remained in the De Caro orchestra until 1953.