1. Introduction

Our

previous excursion into tango harmony introduced minor keys—more

specifically, the exploitation of relative major and minor keys as a

means of contrasting formal structures for musical variety (see A Brief Harmony of Tango, Part III).

Relative major and minor keys use the same key signature but the

respective tonics are formed on different scale degrees as, for

example, C-Major and a-minor, which have no accidentals in the key

signature. There is, however, another kind of major-minor

relationship that composers of tangos frequently employed to express

tonal contrast: parallel major and minor keys.

Example 8: El Apronte, Section B, Consequent Phrase

© 2018 Wolfgang Freis

1.1 Parallel Major-Minor Keys

Parallel

major and minor keys build their tonic on the same scale degree, but

they have different key signatures. For example, D-major carries two

sharp accidentals in the key signature, whereas d-minor shows one

flat.

Example 1: Parallel keys, D-major and d-minor

1.2. Chromaticism

With

respect to their tonality, parallel major and minor keys are more

distantly related to each other than relative keys. However, for the

listener, a switch from one parallel key to the other is not

necessarily perceived as a change of key. Since the tonic chords are

built on the same scale degree, the switch sounds more like a change

of mood—from cheerful major to somber minor, or vice versa—rather

than a move into a distant key.

In

tonal music, changes from a major to a minor chord, or vice versa,

are not uncommon. They are often called “chromatic alterations”

in music theory . “Chromatic” derives its name from the Greek

word “chroma”, meaning “color”. Hence, chromatic alterations

lend “color” to harmony, thus intensifying and enhancing it.

Chromaticism

denotes the presence of one or more pitches that are not naturally

part of a key. It can appear harmonically or melodically. Melodic

chromaticism is an application of the chromatic scale. Unlike any

other type of scale, the chromatic scale consists entirely of

half-tone steps.

Example 2: Chromatic Scale

Since

major and minor keys are defined by a characteristic (natural)

distribution of semi- and whole-tone steps, a chromatic scale by

itself is ambivalent in relation to any harmony.

An

instance of harmonic chromaticism usually takes the form of a

chromatically altered chord, that is, one or more tones of the chord

are raised or lowered by a semitone. In music theory such situations

are often explained as the “borrowing” of a chord from another

key. We will encounter two examples in the analyses below.

Chromaticism

weakens a tonality since it dissolves the natural distribution of

whole- and half-tone steps through which a major or minor key is

created. For this reason, it is often used in tonal music as a

bridge between distantly related keys. It was also a common device

used in many tangos, especially those whose formal structure was

related to parallel major and minor keys. Examples of both melodic

and harmonic chromaticism can be found in Firpo's El Apronte.

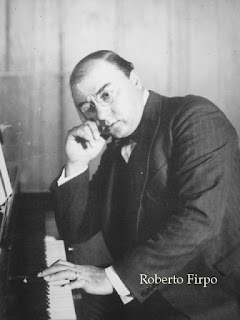

2. Roberto Firpo's El Apronte

El

Apronte was performed for the

first time in 1914 at the first carnival dance of the internists at

the Hospital of San Roque (La Plata). It was Firpo's second tango

milonga, a musical form that

Francisco Canaro said to have created with his tango Pinta

brava, written one year before

El Apronte.

The

formal organization is typical for an instrumental tango of that

period. It consists of three discrete sections (hereafter referred to

as A, B, and C, respectively), of which the third one is labelled

“trio”. The

trio, as customary, is a contrasting portion: whereas sections

A and B exhibit short melodic melodic motifs in a jolted rhythmic

style, section C, the trio, features a long arching melody that the

composer highlighted by setting it as a violin solo.

The

three sections of El Apronte

are each 16 measures long and evenly structured. Each section can be

subdivided into an antecedent and consequent phrases of 8 measures,

and each eight-measure phrase is, in turn, made up of two motives of

four measures.

3. Sections and Keys

The

key signatures (f-sharp and c-sharp for sections A and C, b-flat for

section B) and final chords (D-major for sections A and C, d- minor

for section B) indicate that sections A and C are tonally in D-major,

whereas section B is in d-minor. A more detailed analysis of the

harmonic progressions within each section confirms this view. The

harmonies oscillate, as it were, between tonic and dominant and thus

leave no doubt what the key of the section is: it is either D-major

or d-minor, respectively.

3.1 The Antecedent Phrases

The

antecedent phrase of section A begins and ends on the dominant. Each

occurrence of the dominant is followed by a resolution to the tonic

and thus the key of D-major is established. (Tonic and dominant are

indicated as I and V, respectively, in the following example.)

Example 3: El Apronte, Section A, Antecedent Phrase

In

section B, the key switches to d-minor, but an alternation of

dominant and tonic chords is characteristic of the harmonic

progressions as well. The final chord of the antecedent phrase is

preceded by a diminished seventh chord (indicated as VIIº in the

example), but this chord may be considered simply a variation of the

dominant or, perhaps better said, an alteration and intensification

of the dominant harmony.

Example 4: El Apronte, Section B, Antecedent Phrase

Section

C shows the same picture of a clear tonal focus, here again in D-major.

The antecedent phrase is once again an alternation of dominant and

tonic chords.

Example 5: El Apronte, Section C, Antecedent Phrase

In

summary, the antecedent phrases of the three sections can be

described as a series of dominant and tonic harmonies in their

respective key, D-major or D-minor. From the outset, every section

establishes a clear focus on its tonic, be it D-major or D-minor.

3.2 The Consequent Phrases

While

an alternation of dominant and tonic chords is an unequivocal

indicator of a key, it does not, strictly speaking, establish a key.

For this, a cadence is needed, and a cadence usually involves at

least one other harmony besides the tonic and dominant: the

subdominant. Moreover, cadences serve a double purpose: they not only

establish a key, they also mark the end of phrases. It comes as no a

surprise, then, to find cadences in the consequent phrases of El

Apronte, particularly in the second motives at the end of each

section.

Section

A, for example, ends with a textbook example of a cadence in a major

key. Whereas the first motive of the consequent phrase is a

repetition of the antecedent phrase, the second motif introduces a

new harmony, the subdominant (indicated as IV in the example) and

thus initiates the final cadence of the section.

Example 6: El Apronte, Section A, Consequent Phrase

All

harmonies before this cadence were either the tonic or the dominant.

The appearance of the subdominant at this point is significant, not

only because it is a new harmony, but also because it is a model for

the following section. Sections B and C also feature completely new

harmonies in places corresponding to Section A. However, they are at

the same time examples of harmonic chromaticism and will be discussed

below.

3.3 Section A: Melodic Chromaticism

Our

previous assertion that the formal structure of El Apronte

consists of three sections of 16 measures length each is not quite

correct. The first section is actually preceded by an introduction of

three measures. This introduction is a distinct segment since its

melodic content (a simple descending chromatic scale) has nothing in

common with the melodies of the proper section. The composer

indicated, however, that it be repeated with every repetition of the

section and, thus, it should be considered a part of section A.

Example 7: El Apronte, Section A, Introduction

The

introduction does not affect, however, the tonality of the section.

We have noted above that a chromatic scale is neutral with respect to

major and minor tonalities since it consists entirely of half-tone

steps. This becomes evident in the introduction. Its opening chord is

a dominant, and the proper section A starts on this harmony as well.

Two measures of the chromatic scale do not change the harmony: since

all steps are semitones, no reference to any other harmony is made.

The chromatic scale is in

this case mere “filler material”, as it were.

|

| Illustration 1: El Apronte, Section A, Introduction |

While

the introduction has no influence on the unfolding harmony, it is

significant in respect to the musical form. It is an

attention-grabbing moment at the beginning of the piece, as well as

with every repetition as it signals audibly the recapitulation of

section A. Yet, we believe, it is not just simply an embellishment to

make the piece sound engaging, it is also an allusion to the

instances of harmonic chromaticism in sections B and C.

3.4 Sections B and C: Harmonic Chromaticism

Instances

of melodic chromaticism can be found in sections B and C as well;

however, they are not as prominent and extensive as the introduction

to section A. Sections B and C show instead conspicuous examples of harmonic

chromaticism.

Section

B is set in D-minor, in contrast to the D-major key of the sections

surrounding it. The change of key is a simple switch from one key to

the other, a fact that is noteworthy by itself. There is no harmonic

preparation or transition: section A ends in D-major and section B

begins in D-minor. The change back to D-major in section C is carried

out just as perfunctory.

It

was mentioned above that the phrase structure of the sections is very

regular: 16 measures divided into two antecedent and consequent

phrases of eight measures which, in turn, can be divided into motifs

of four measures. Within each section, the first motif of a

consequent phrase is repeated as the first motif of the consequent

phrase. (Section C diverges slightly from this model, as we shall

see.) The second motif of the consequent phrases, however, differs

markedly from the antecedent phrase: it brings about the final

cadence of the section and introduces a new harmony that has not been

heard before.

In

section A, it was the subdominant (IV, a G-major chord) that

initiated a standard major-key cadence. In section B, however, which

is set in D-minor, we encounter neither the major nor minor form of

the subdominant (a G-major or g-minor chord, respectively) but an

E-flat-major chord instead (indicated as N in the following example).

Example 8: El Apronte, Section B, Consequent Phrase

An

E-flat-major chord does not naturally appear in D-minor. It can only

be created by chromatically lowering the second scale degree from E

to E-flat. Hence, it represents a “chromatic alteration” or

harmonic chromaticism. In the context of a cadence on D, an E-flat-major

chord is, however, not an uncommon occurrence in D-minor (or D-major,

for that manner). It is called a “Neapolitan” chord in music

theory and signifies “a major chord built on the chromatically

lowered second scale degree in the functional context of a

subdominant”. In

the preceding example, the “Neapolitan” initiates the final cadence of

section B, just as the subdominant did in section A.

The

consequent phrase of section C shows analogous chord progression. However,

it occurs two measures earlier within the first motif. Here we find

another chord that is not natural to the key and can only be obtained

through chromatic alteration. This time it is a B-flat-major chord

(indicated as N/V in the following example).

Example 8: El Apronte, Section c, Consequent Phrase

In

contrast to the “Neapolitan” progression in section B, there

exists no term in music theory to signify the B-flat-major chord in

this context. Yet, the analogy between the two progressions cannot be

overlooked: the B-flat-major chord resolves to the dominant a half

tone lower, just as the “Neapolitan” chord resolves to the tonic

a half step lower. Hence, one could describe this B-major-chord as a

“Neapolitan chord of the dominant” (hence the symbol N/V).

4. Conclusion

As

in our previous harmonic analyses of tango, we have encountered a

short piece of entertainment music that demonstrates a surprising

complexity in its composition. From a harmonic point of view, the

material that we have uncovered is not innovative. It belongs to the

common harmonic language of Western music. However, the way it was

applied is remarkable. Firpo created a small musical jewel that is

extremely well thought out and highly structured. This is a kind of

composition that one would expect in serious rather than dance music.

From

its beginnings, tango was marketed as a kind of urban folk music,

created by people with little or no musical training. Composers like

Firpo and those we looked at in our preceding analyses (Arturo de

Bassi, Ángel Villoldo, Eduardo Arolas, but the same it true for many

other tango composers) bespeak a different picture. An analysis of

their compositions shows that they understood what their colleagues

of serious music were doing and applied it in their own work.

Example 8: El Apronte, Recorded 1926 by the Orquesta Roberto Firpo.

© 2018 Wolfgang Freis

No comments:

Post a Comment