(Englisch Version)

1. Einleitung

Unsere

letzte Abhandlung einer Harmonielehre des Tangos beschäftigte sich

mit den Molltonarten—genauer gesagt: die Verwendung der

Paralleltonarten als ein Mittel der Kontrastierung formaler

Strukturen. Die Paralleltonarten in Dur und Moll haben die gleichen

Vorzeichen, haben aber ihren Grundton, die Tonika, auf

unterschiedlichen Tonleiterstufen. So werden z.B. C-Dur und a-Moll

ohne Vorzeichen notiert. Es gibt allerdings noch eine andere

Beziehung zwischen Dur- und Molltonarten, die von Tango-Komponisten

oft als Mittel der tonalen Kontrastierung eingesetzt wurde: die

Varianttonarten.

1.1 Die Varianttonarten in Dur und Moll

Varianttonarten in Dur und Moll haben ihre Tonika auf der selben Tonleiterstufe, unterscheiden sich aber in den Vorzeichen. So werden D-Dur zwei Kreuze vorgesetzt, während D-Moll ein B aufzeigt.

Beispiel 1: Varianttonarten D-Dur und D-Moll

1.2. Chromatik

Im Vergleich zu den Paralleltonarten ist der Verwandtschaftsgrad der Varianttonarten entfernter. Trotzdem wird ein Wechsel zwischen Varianten von den Hörern nicht unbedingt als Tonartwechsel empfunden. Da die Toniken auf dem selben Grundton beruhen, wirkt ein Übergang in die Varianttonart oft nur als Stimmungs- statt eines Tonartwechsels empfunden (vom heiteren Dur ins düstere Moll oder umgekehrt ).

Schwankungen zwischen Dur- und Mollvarianten sind in der tonalen Musik nicht ungewöhnlich. Sie werden in der Musiktheorie als „chromatische Veränderungen“ bezeichnet. „Chromatisch“ geht auf das griechische Wort für Farbe, „chroma“, zurück. Chromatische Veränderungen verstärken und bereichern Akkordverbindungen, indem sie ihnen zusätzliche Nuancen verleihen.

Chromatik ergibt sich durch die Anwesenheit eines oder mehrerer Töne, die naturgemäß nicht in der gegebenen Tonart vorkommen. Sie kann melodisch oder harmonisch auftreten. Melodische Chromatik zeigt sich in der Anwendung der chromatischen Tonleiter, die im Gegensatz allen anderen Tonleitern nur aus Halbtonschritten besteht.

Schwankungen zwischen Dur- und Mollvarianten sind in der tonalen Musik nicht ungewöhnlich. Sie werden in der Musiktheorie als „chromatische Veränderungen“ bezeichnet. „Chromatisch“ geht auf das griechische Wort für Farbe, „chroma“, zurück. Chromatische Veränderungen verstärken und bereichern Akkordverbindungen, indem sie ihnen zusätzliche Nuancen verleihen.

Chromatik ergibt sich durch die Anwesenheit eines oder mehrerer Töne, die naturgemäß nicht in der gegebenen Tonart vorkommen. Sie kann melodisch oder harmonisch auftreten. Melodische Chromatik zeigt sich in der Anwendung der chromatischen Tonleiter, die im Gegensatz allen anderen Tonleitern nur aus Halbtonschritten besteht.

Beispiel 2: Chromatische Tonleiter

Da Dur-und Molltonarten durch eine charakteristische (natürliche) Verteilung von Ganz- und Halbtonschritten bestimmt werden, verhält sich eine chromatische Tonleiter zu jedweder Harmonie neutral.

Harmonische Chromatik tritt als chromatisch veränderte Akkorde in Erscheinung, d.h., ein oder mehrere Töne eines Akkordes werden Halbtonschritte erhöht oder erniedrigt. Die Musiktheorie legt solche Situationen oft als ein „Ausleihen“ eines Akkordes von einer anderen Tonart aus. Wir werden zwei Beispiele in der folgenden Analyse antreffen.

Tonalität wird durch Chromatik abgeschwächt, da es die natürliche Verteilung der Ganz- und Halbtonschritte, aus denen sich eine Dur- oder Molltonart zusammensetzt, auflöst. Deshalb wird sie in der tonalen Musik auch oft dazu herangezogen, um Verbindungen zwischen entfernt verwandten Harmonien zu überbrücken. Chromatik findet sich auch in vielen Tangos—besonders in solchen, deren formale Struktur mit den Varianttonarten in Beziehung steht. In Roberto Firpos El Apronte zeigen sich melodische wie harmonische Chromatik.

Harmonische Chromatik tritt als chromatisch veränderte Akkorde in Erscheinung, d.h., ein oder mehrere Töne eines Akkordes werden Halbtonschritte erhöht oder erniedrigt. Die Musiktheorie legt solche Situationen oft als ein „Ausleihen“ eines Akkordes von einer anderen Tonart aus. Wir werden zwei Beispiele in der folgenden Analyse antreffen.

Tonalität wird durch Chromatik abgeschwächt, da es die natürliche Verteilung der Ganz- und Halbtonschritte, aus denen sich eine Dur- oder Molltonart zusammensetzt, auflöst. Deshalb wird sie in der tonalen Musik auch oft dazu herangezogen, um Verbindungen zwischen entfernt verwandten Harmonien zu überbrücken. Chromatik findet sich auch in vielen Tangos—besonders in solchen, deren formale Struktur mit den Varianttonarten in Beziehung steht. In Roberto Firpos El Apronte zeigen sich melodische wie harmonische Chromatik.

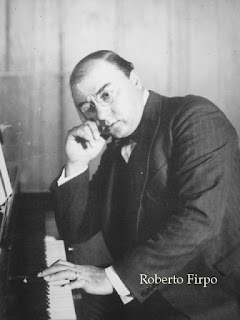

2. Roberto Firpos El Apronte

El

Apronte wurde im Karneval 1914

anläßlich des ersten Balls der Internisten des Krankenhauses San

Roque (La Plata) uraufgeführt. Es war Firpos zweiter tango

milonga, eine Tango-Form, dessen

Kreation Francisco Canaro mit Pinta brava

(1913) für sich in Anspruch nahm.

Der

formale Aufbau ist typisch für einen instrumentalen Tango dieser

Epoche. Er besteht aus drei Teilen unabhängigen Sätzen (im

Folgenden als A, B oder C gekennzeichnet), von denen der dritte als

„Trio“ gekennzeichnet ist. Das Trio ist, wie üblich, ein

kontrastierender Teil. Die Sätze A und B weisen kurze, abgehackte

melodische Motive auf, während Satz C, das Trio, langgestreckte

melodische Bögen bietet, die der Komponist noch dadurch betonte,

indem er sie als Geigensolo arrangierte.

Die

drei Sätze sind gleichmäßig gegliedert und bestehen aus jeweils 16

Takten. Sie können ihrerseits in zwei Phrasen, einen Vorder- und

einen Nachsatz, von jeweils 8 Takten aufgeteilt werden. Die Phrasen

setzen sich dann aus zwei vier-taktigen Motiven zusammen.

3. Sätze und Tonarten

Die Vorzeichen (Fis und Cis in den Sätzen A und C, B in Satz B) und Schlussakkorde (D-Dur in A und C, D-Moll in B) lassen darauf schließen, dass A und C in D-Dur geschrieben sind, während Satz B in D-Moll steht. Eine eingehendere Analyse des harmonischen Ablaufs innerhalb der einzelnen Sätze bestätigt diesen Eindruck. Die Harmonien pendeln sozusagen zwischen der Tonika und Dominante und verankern somit die Tonalität klar in D-Dur beziehungsweise D-Moll.

3.1 Die Vordersätze

Der

Vordersatz des A Satzes beginnt und endet mit der Dominante. Auf

jedes Erscheinen einer Dominante folgt eine Auflösung zur Tonika,

und damit wird die Tonart auf D-Dur festgesetzt. (Tonika und

Dominante sind im folgenden Beispiel als I beziehungsweise V

markiert.)

Beispiel 3: El Apronte, Satz A, Vordersatz

Mit

Satz B wechselt die Tonart ins D-Moll. Für den Vordersatz ist auch

hier eine Wechselfolge von Akkorden auf der Tonika und Dominante

charakteristisch. Dem Schlussakkord des Vordersatzes geht ein

verminderter Septakkord voran (im Beispiel als VIIº angezeigt), aber

dieser Akkord ist lediglich eine Variante der Dominante, oder, anders

ausgedrückt, eine Abwandlung und Verschärfung der Dominante.

Beispiel 4: El Apronte, Satz B, Vordersatz

Satz C weist ebenso wie die vorangegangenen Sätze einen eindeutigen tonalen Schwerpunkt auf—hier wieder in D-Dur. Der Vordersatz ist abermals eine Wechselfolge von Akkorden auf der Tonika und Dominante.

Beispiel 5: El Apronte, Satz C, Vordersatz

Insgesamt lassen sich die drei Vordersätze als eine Aufeinanderfolge von Tonika- und Dominantakkorden in der jeweiligen Tonart des Satzes beschreiben. Jeder der Vordersätze baut von Anbeginn einen harmonischen Schwerpunkt auf der Tonika auf, sei es nun D-Dur oder D-Moll.

3.2 Die Nachsätze

Obwohl

eine Wechselfolge von Dominanten und Toniken ein klarer Hinweis auf

eine Tonart ist, so wird sie, genau genommen, dadurch jedoch nicht

festgelegt. Dazu bedarf es einer Kadenz, welche normalerweise noch

einer weiteren Harmonie neben der Tonika und Dominante bedarf: die

Subdominante. Darüber hinaus dienen Kadenzen einem doppelten Zweck:

sie bestimmen nicht nur die Tonart, sondern markieren auch den

Abschluss von Melodien und Phrasen. Es überrascht daher nicht, dass

alle Nachsätze in El Apronte mit Kadenzen enden.

Satz

A schließt zum Beispiel mit einer exemplarischen Dur-Kadenz ab. Das

erste Motiv des Nachsatzes ist eine Wiederholung des ersten Motivs

des Vordersatzes. Das zweite Motiv führt zum ersten Mal einen

anderen Akkord als die Tonika oder Dominante ein—die Subdominante

(im folgenden Beispiel als IV angezeigt)—und leitet damit die

Schlusskadenz dieses Satzes ein.

Beispiel 6: El Apronte, Satz A, Nachsatz

Alle der Kadenz vorangehenden Harmonien bewegten sich ausschließlich zwischen Tonika und Dominante. Das Auftreten der Subdominante an diesem Punkt ist bedeutend: nicht nur, weil es eine neue Harmonie präsentiert, sondern auch, weil es eine Vorlage für die folgenden Sätze darstellt. Auch in den Sätzen B und C finden sich vollkommen neue Harmonien in der Position, die dem Satz A entspricht. Diese sind aber gleichzeitig Beispiele harmonischer Chromatik und werden unten besprochen.

3.3 Satz A: Melodische Chromatik

Unsere frühere Bemerkung, dass die formale Struktur von El Apronte aus drei Sätzen von jeweils 16 Takten besteht, war nicht vollends korrekt. Dem ersten Satz ist eine Einleitung von drei Takten vorangesetzt. Diese Einleitung bildet einen eigenständigen Abschnitt, da der melodische Inhalt (eine einfache absteigende chromatische Tonleiter) nichts mit dem des eigentlichen Satzes gemeinsam hat. Der Komponist hat sie aber so notiert, dass sie mit jeder Wiederholung des Satzes neu gespielt wird. Die Einleitung ist also ein fester Bestandteil des eigentlichen Satzes.

Beispiel 7: El Apronte, Satz A, Einleitung

Die Einleitung hat allerdings keinen Einfluss auf die Tonalität des Satzes. Wir haben oben darauf hingewiesen, dass sich eine chromatische Tonleiter im Bezug auf Dur- oder Molltonalitäten neutral verhält, da sie durchweg aus Halbtonschritten besteht. Dies zeigt sich deutlich hier in der Einleitung. Der erste Akkord der Einleitung sowie der erste des eigentlichen Satzes stehen beide auf der Dominante. Die chromatische Tonleiter, die die beiden Takte zwischen ihnen ausfüllt, ändert die Wahrnehmung der Harmonie nicht. Da jede Tonfolge ein Halbtonschritt ist, kann kein Bezug auf eine andere Harmonie hergestellt werden. Die chromatische Tonleiter ist in diesem Fall sozusagen nur „Füllmaterial“.

Illustration 1: El Apronte, Satz A, Einleitung

Obwohl die Einleitung keinen Einfluss auf die sich entwickelnde Harmonie hat, ist sie dennoch im Hinblick auf die formale Gestaltung des Stückes von Bedeutung. Als hervorstechende melodische Figur signalisiert sie beim ersten Erscheinen den Beginn des Satzes A, und mit jeder Wiederholung seine Repetition. Wir gehen davon aus, dass diese Figur nicht nur der Verzierung und Ausschmückung dient, sondern auch eine Anspielung auf die Chromatik der folgenden Sätze ist und damit formbildenden Charakter hat.

3.4 Harmonische Chromatik in den Sätzen B und C

In den Sätzen B und C sind auch Beispiele melodischer Chromatik anzutreffen, sie sind aber nicht so markant und ausgedehnt wie im Satz A. Dagegen finden sich in den letzten beiden Sätzen auffallende Beispiele harmonischer Chromatik.

Satz B ist in D-Moll gesetzt, im Gegensatz zu den beiden Ecksätzen in der Varianttonart D-Dur. Der Tonartwechsel ist ein einfacher Schritt von einer Tonart in die andere—ein Sachverhalt, der an sich bemerkenswert ist. Satz A endet in D-Dur, und Satz B beginnt in D-Moll ohne Vorbereitung oder Übergang. Der Wechsel zurück zu D-Dur in Satz C wird ebenso beiläufig vollzogen.

Oben wurde erwähnt, dass die Phrasierungsstruktur von El Apronte sehr regelmäßig verläuft: die sechzehn-taktigen Sätze teilen sich in Vorder- und Nachsätze mit jeweils acht Takten auf, die sich dann wiederum vier-taktige Motive zergliedern lassen. In jedem Satz ist das erste Motiv des Nachsatzes eine Wiederholung des ersten Motivs des Vordersatzes. (Satz C weicht, wie wir sehen werden, geringfügig von diesem Modell ab.) Das zweite Motiv des Nachsatzes unterscheidet sich allerdings maßgeblich von dem des Vordersatz: Es leitet die Schlusskadenz des Satzes ein und fügt eine neue Harmonie ein, die bis dahin noch nicht berührt wurde.

Im Satz A war es die Subdominante (IV, ein G-Dur-Akkord), die eine standardmäßige Dur-Schlusskadenz einleitete. Im Satz B, der in D-Moll geschrieben ist, trifft man aber weder die Dur- noch die Moll-Form der Subdominante (einen G-Dur- beziehungsweise G-Moll-Akkord) an, sondern einen Es-Dur-Akkord (im folgenden Beispiel als N markiert).

Satz B ist in D-Moll gesetzt, im Gegensatz zu den beiden Ecksätzen in der Varianttonart D-Dur. Der Tonartwechsel ist ein einfacher Schritt von einer Tonart in die andere—ein Sachverhalt, der an sich bemerkenswert ist. Satz A endet in D-Dur, und Satz B beginnt in D-Moll ohne Vorbereitung oder Übergang. Der Wechsel zurück zu D-Dur in Satz C wird ebenso beiläufig vollzogen.

Oben wurde erwähnt, dass die Phrasierungsstruktur von El Apronte sehr regelmäßig verläuft: die sechzehn-taktigen Sätze teilen sich in Vorder- und Nachsätze mit jeweils acht Takten auf, die sich dann wiederum vier-taktige Motive zergliedern lassen. In jedem Satz ist das erste Motiv des Nachsatzes eine Wiederholung des ersten Motivs des Vordersatzes. (Satz C weicht, wie wir sehen werden, geringfügig von diesem Modell ab.) Das zweite Motiv des Nachsatzes unterscheidet sich allerdings maßgeblich von dem des Vordersatz: Es leitet die Schlusskadenz des Satzes ein und fügt eine neue Harmonie ein, die bis dahin noch nicht berührt wurde.

Im Satz A war es die Subdominante (IV, ein G-Dur-Akkord), die eine standardmäßige Dur-Schlusskadenz einleitete. Im Satz B, der in D-Moll geschrieben ist, trifft man aber weder die Dur- noch die Moll-Form der Subdominante (einen G-Dur- beziehungsweise G-Moll-Akkord) an, sondern einen Es-Dur-Akkord (im folgenden Beispiel als N markiert).

Beispiel 8: El Apronte, Satz B, Nachsatz

Ein Es-Dur-Akkord gehört nicht zum natürlichen Akkordbestand in D-Moll. Er kann nur durch eine chromatische Erniedrigung der zweiten Tonleiterstufe vom E zum Es erzeugt werden und stellt somit eine „chromatische Veränderung“ oder chromatische Harmonik dar. Im Zusammenhang einer Schlusskadenz auf D ist ein Es-Dur-Akkord allerdings keine Seltenheit. In der Musiktheorie wird er „Neapolitaner“ genannt und bezeichnet „einen Dur-Akkord auf der erniedrigten zweiten Stufe im funktionalen Zusammenhang der Subdominante“. Der „Neapolitaner“ leitet hier die Schlusskadenz des Satzes B ein, genauso wie es die Subdominante im Satz A tat.

Der Nachsatz des Satzes C zeigt eine analoge Akkordverbindung, jedoch beginnt sie schon im ersten Motiv zwei Takte früher. Auch hier findet sich ein Akkord, der nicht zum natürlichen Akkordbestand der Tonart gehört und nur durch chromatische Veränderung erzeugt werden kann. Diesmal handelt es sich um einen B-Dur-Akkord (im folgenden Beispiel als N/V markiert).

Der Nachsatz des Satzes C zeigt eine analoge Akkordverbindung, jedoch beginnt sie schon im ersten Motiv zwei Takte früher. Auch hier findet sich ein Akkord, der nicht zum natürlichen Akkordbestand der Tonart gehört und nur durch chromatische Veränderung erzeugt werden kann. Diesmal handelt es sich um einen B-Dur-Akkord (im folgenden Beispiel als N/V markiert).

Beispiel 9: El Apronte, Satz C, Nachsatz

Im Gegensatz zum oben besprochenen „Neapolitaner“ gibt es in der Musiktheorie keinen Begriff, um einen B-Dur-Akkord in diesem Zusammenhang zu kennzeichnen. Dennoch läßt sich die Analogie zwischen den beiden Progressionen nicht übersehen: Der B-Dur-Akkord löst sich zur einen Halbtonschritt tiefer gelegenen Dominante auf; genau so, wie sich der „Neapolitaner“ zur einen Halbtonschritt tiefer gelegenen Tonika auflöste (daher die Markierung N/V).

4. Schlussfolgerung

Wie in unseren vorangegangenen Analysen, sind wir auf ein kurzes Stück Unterhaltungsmusik gestoßen, dass in seiner Komposition eine erstaunliche Komplexität aufweist. Aus der Sicht der Harmonie ist das Material, das wir vorfanden, nicht neuartig; es entstammt den allgemein verbreiteten harmonischen Ausdrucksformen der europäischen Musik. Die Anwendung—d.h., wie es in die Komposition eingebaut wurde—ist allerdings beachtenswert. Firpo konstruierte ein kleines musikalisches Schmuckstück, eine hervorragend durchdachte und aufgebaute Komposition, die man eher in ernster als in Tanzmusik erwarten würde.

Tango wurde von Anbeginn als eine Art urbaner Volksmusik vermarktet, die von Personen ohne oder mit wenig musikalischer Ausbildung erschaffen wurden. Komponisten wie Firpo und die unserer vorangegangenen Analysen (Arturo de Bassi, Ángel Villoldo, Eduardo Arolas, und viele andere) lassen ein anderes Bild erkennen. Eine Auswertung ihrer Kompositionen zeigt, dass sie mit den Ideen ihrer Kollegen aus der ernsten Musik durchaus vertraut waren und sich mit ihnen in ihren eigenen Werken auseinandersetzten.

Tango wurde von Anbeginn als eine Art urbaner Volksmusik vermarktet, die von Personen ohne oder mit wenig musikalischer Ausbildung erschaffen wurden. Komponisten wie Firpo und die unserer vorangegangenen Analysen (Arturo de Bassi, Ángel Villoldo, Eduardo Arolas, und viele andere) lassen ein anderes Bild erkennen. Eine Auswertung ihrer Kompositionen zeigt, dass sie mit den Ideen ihrer Kollegen aus der ernsten Musik durchaus vertraut waren und sich mit ihnen in ihren eigenen Werken auseinandersetzten.

Beispiel 10: El Apronte. Aufgenommen 1926 vom Orquesta Roberto Firpo.

© 2018 Wolfgang Freis