|

| Eduardo Arolas |

1. Einleitung

1.1 Die Moll-Tonarten

Zuvor untersuchten wir zwei fundamentale Aspekte der Tonalität: die Beziehungen der Dominante und Subdominante zur Tonika. Wir haben gesehen, wie die Dominant- und Subdominant-Funktionen angewendet wurden, um eine Tonart aufzubauen, und als musikalischer Kontrast eingesetzt wurden, um eine Komposition interessanter zu gestalten. Der Einfachheit halber wurden nur Stücke in Dur-Tonarten besprochen. Es gibt jedoch noch eine andere Tonartengattung, die für den Tango von besonderer Bedeutung ist: die Moll-Tonarten.

Dur- und Moll-Tonarten unterscheiden sich durch verschiedenartige Tonleitern, d.h., durch eine voneinander abweichende Verteilung der Halb- und Ganztonschritte. Daraus ergeben sich zwangsläufig auch andere Harmonien. Der Akkord auf der Tonika z.B. entspricht der Bezeichnung der Tonart und ist entweder Dur oder Moll.

Alle Dur- und Moll-Tonleitern bestehen aus fünf Ganz- und zwei Halbtonschritten. In der Dur-Tonleiter befinden sich die Halbtonschritte zwischen der dritten und vierten, beziehungsweise der siebten und achten Stufe. (In den folgenden Beispielen sind die Halbtonschritte durch Bindungsbögen über den betreffenden Noten angezeigt. Der Tonika-Akkord erklingt am Ende jedes Beispiels.) Die Reihenfolge der Ganz- und Halbtonschritte bleibt bei auf- und absteigender Bewegung die gleiche.

Dur- und Moll-Tonarten unterscheiden sich durch verschiedenartige Tonleitern, d.h., durch eine voneinander abweichende Verteilung der Halb- und Ganztonschritte. Daraus ergeben sich zwangsläufig auch andere Harmonien. Der Akkord auf der Tonika z.B. entspricht der Bezeichnung der Tonart und ist entweder Dur oder Moll.

Alle Dur- und Moll-Tonleitern bestehen aus fünf Ganz- und zwei Halbtonschritten. In der Dur-Tonleiter befinden sich die Halbtonschritte zwischen der dritten und vierten, beziehungsweise der siebten und achten Stufe. (In den folgenden Beispielen sind die Halbtonschritte durch Bindungsbögen über den betreffenden Noten angezeigt. Der Tonika-Akkord erklingt am Ende jedes Beispiels.) Die Reihenfolge der Ganz- und Halbtonschritte bleibt bei auf- und absteigender Bewegung die gleiche.

In der (natürlichen) Moll-Tonleiter befinden sich die Halbtonschritte zwischen der zweiten und dritten, beziehungsweise der sechsten und siebten Stufe.

Die Lage des ersten Halbtonschrittes bestimmt den Dur- oder Moll-Charakter des Tonika-Akkordes. Liegt der Halbton zwischen der dritten und vierten Stufe der Dur-Tonleiter, so wird der Tonika-Akkord zwangsläufig zum Dur-Akkord. Dementsprechend bewirkt die Moll-Tonleiter mit ihrem ersten Halbtonschritt zwischen der zweiten und dritten Stufe einen Moll-Akkord auf der Tonika.

Es ist allerdings eine Eigenart der Moll-Tonleiter, dass sie selten in ihrer natürlichen Form gebraucht wird. Aus melodischen und harmonischen Gründen werden die sechste und siebente Stufe bei aufsteigender Bewegung um einen Halbton erhöht, und dann in absteigender Bewegung wieder erniedrigt. Diese Art der Tonleiter wird als „melodische Moll-Tonleiter“ bezeichnet.

Es ist allerdings eine Eigenart der Moll-Tonleiter, dass sie selten in ihrer natürlichen Form gebraucht wird. Aus melodischen und harmonischen Gründen werden die sechste und siebente Stufe bei aufsteigender Bewegung um einen Halbton erhöht, und dann in absteigender Bewegung wieder erniedrigt. Diese Art der Tonleiter wird als „melodische Moll-Tonleiter“ bezeichnet.

Das Beispiel veranschaulicht, dass die harmonischen Möglichkeiten einer Moll-Tonart größer sind, als die einer Dur-Tonart. In Dur sind z.B. die Subdominante und Dominante immer Dur-Akkorde. In Moll können sie aber als Dur- oder Moll-Akkorde erscheinen, je nachdem, ob sie in einem melodisch auf- oder absteigendem Zusammenhang stehen.

Dur- und Moll-Tonarten mit den gleichen Vorzeichen werden als Paralleltonarten bezeichnet. Ihre Verwandtschaft ist offensichtlich: beide Tonarten haben die Akkorde der natürlichen Tonleiter gemeinsam. Jede Paralleltonart hat aber ihre eigene Subdominante und Dominante und ist daher eine eigenständige Tonarten. Das folgende Beispiel gibt die Tonleiterstufen der Paralleltonarten F-Dur und D-Moll wieder. Die Tonika-Stufen sind in Kästchen eingefasst; Subdominante und Dominante werden durch eckige Klammern über oder unter den Stufenziffern angezeigt.

1.2 Parallele Dur- und Moll-Tonarten

Dur- und Moll-Tonarten mit den gleichen Vorzeichen werden als Paralleltonarten bezeichnet. Ihre Verwandtschaft ist offensichtlich: beide Tonarten haben die Akkorde der natürlichen Tonleiter gemeinsam. Jede Paralleltonart hat aber ihre eigene Subdominante und Dominante und ist daher eine eigenständige Tonarten. Das folgende Beispiel gibt die Tonleiterstufen der Paralleltonarten F-Dur und D-Moll wieder. Die Tonika-Stufen sind in Kästchen eingefasst; Subdominante und Dominante werden durch eckige Klammern über oder unter den Stufenziffern angezeigt.

|

| Tonleiterstufen der Paralleltonarten D-Moll und F-Dur |

Das Beispiel verdeutlicht, dass Paralleltonarten sich ähnlich sind und sich eine Anzahl des Klangmaterials (Akkorde) teilen. Andererseits sind sie eigenständige Strukturen, denn die Akkorde haben eine andere Funktion in Bezug auf die Tonika. Die Dominante der Moll-Tonart (d: V im Beispiel) kann in der parallelen Dur-Tonart (F: III im Beispiel) nur eine Nebendominante sein. Die Wechselbeziehung zwischen Tonika und Dominante ist festgelegt und spezifisch für eine Tonart. (Nebendominanten wurden in Eine kleine Tango-Harmonielehre, II besprochen.)

Unsere vorangegangen Abhandlungen über Harmonie in Tango-Musik zeigten, dass Komponisten Dominant- und Subdominant-Tonarten als Kontrast zur Haupttonart einsetzten. Dadurch wurde die formale Struktur des Stückes unterstrichen und das klangliche Erlebnis bereichert. In diesen Fällen waren sowohl die Tonika als auch die Kontrasttonarten in Dur. Moll-Tonarten können natürlich auch für solche Kompositionsstrukturierung eingesetzt werden. In der Tat war es sogar eine gebräuchlicher Methode als Tonarten der gleichen Gattung miteinander zu kontrastieren.

Der Grund für diese Bevorzugung liegt vermutlich darin, dass der Kontrast zwischen Dur und Moll einerseits auffälliger ist, und andererseits die Harmonien reichhaltiger und ausdrucksvoller werden. Zudem bot sich der klangliche Unterschied eines heiteren Durs und düsteren Molls dazu an, die melancholische Stimmung vieler Tangotexte auszudrücken.

Obwohl so manchem Tangotänzer heute der Name Eduardo Arolas unbekannt ist, würden viele eine gute Anzahl seiner Kompositionen wiedererkennen. Es gibt keine Milonga, auf der man nicht Tangos wie „Comme il faut“, „Derecho viejo“, „Retintín“, „La Guitarrita“ oder eine andere der vielen Kompositionen Arolas zu hören bekommt.

Arolas war ein Bandoneon-Spieler und Komponist, der unter seinen Kollegen hohes Ansehen genoss. Er wurde 1892 in Buenos Aires geboren und verstarb im noch jungen Alter von 32 Jahren in Paris. Es gibt daher von Arolas und seinem Orchester relativ wenige Schallplatten und die wenigen, die uns erhalten blieben, sind primitive Aufnahmen mit schlechter Klangqualität.

Sein erstes Instrument war die Gitarre, die er in den Cafés seiner Heimatstadt spielte,. Er wechselte aber bald zum Bandoneon. Um 1909, als er seinen ersten Tango komponierte („Noche de garufa“), konnte er noch keine Noten lesen, und seine Freunde mussten ihm bei der Niederschrift helfen. 1911 trat er aber in ein Konservatorium ein und studierte dort für drei Jahre Musik. Das Studium schlug sich deutlich in seinen Kompositionen nieder. Seine Stücke—darunter auch Cardos—zeugen von einem experimentierfreudigen Komponisten mit guten Kenntnissen der Musiktheorie.

Cardos ist einer von Arolas weniger bekannten Tangos. Uns sind zwei Aufnahmen bekannt, von denen eine, die wundervolle Version des Orquesta Típica Victor, unten als Beispiel angeführt wird. Da sich im Stück keine Spuren des Habanera-Rhythmus finden, ist anzunehmen, dass Cardos eine der späteren Kompositionen Arolas aus den 20er Jahren ist.

Wie die meisten instrumentalen Tangos aus dem ersten Viertel des 20. Jahrhunderts wurde Cardos in einer dreisätzigen Liedform komponiert. Die Struktur ist äußerst regelmäßig: jeder Satz (hiernach A, B, beziehungsweise C) besteht aus 16 Takten. Jeder Satz ist wiederum in einen Vorder- und Nachsatz von je 8 Takten aufgeteilt.

Diese Aufteilung setzt sich auch in den kleineren Bestandteilen fort: die acht-taktigen Vorder- und Nachsätze bestehen aus zwei vier-taktigen Perioden, und die Perioden ihrerseits aus zwei zwei-taktigen Motiven. Jede Periode endet mit einer Kadenz, von denen die, die am Ende der Nachsätze stehen, stärker sind.

Entsprechend der Vorzeichen und Schlussakkorde sind die Sätze A und B in D-Moll. In beiden Fällen geht dem Schlussakkord eine starke Kadenz voraus, die die Tonalität klar im D-Moll verankert. Satz C zeigt die gleichen Vorzeichen wie die anderen beiden Sätzen, endet aber mit einem F-Dur-Akkord, ebenfalls nach einer starken Kadenz. Dieser Satz steht also in F-Dur, der Paralleltonart zu D-Moll.

Wenn das Stück mit all seinen Wiederholungen gespielt wird (so wie in der Aufnahme des Orquesta Típica Victor, siehe unten), ergibt sich die folgende tonale Anordnung der Sätze:

Unsere vorangegangen Abhandlungen über Harmonie in Tango-Musik zeigten, dass Komponisten Dominant- und Subdominant-Tonarten als Kontrast zur Haupttonart einsetzten. Dadurch wurde die formale Struktur des Stückes unterstrichen und das klangliche Erlebnis bereichert. In diesen Fällen waren sowohl die Tonika als auch die Kontrasttonarten in Dur. Moll-Tonarten können natürlich auch für solche Kompositionsstrukturierung eingesetzt werden. In der Tat war es sogar eine gebräuchlicher Methode als Tonarten der gleichen Gattung miteinander zu kontrastieren.

Der Grund für diese Bevorzugung liegt vermutlich darin, dass der Kontrast zwischen Dur und Moll einerseits auffälliger ist, und andererseits die Harmonien reichhaltiger und ausdrucksvoller werden. Zudem bot sich der klangliche Unterschied eines heiteren Durs und düsteren Molls dazu an, die melancholische Stimmung vieler Tangotexte auszudrücken.

2. Arolas, “El Tigre del Bandoneón”

Obwohl so manchem Tangotänzer heute der Name Eduardo Arolas unbekannt ist, würden viele eine gute Anzahl seiner Kompositionen wiedererkennen. Es gibt keine Milonga, auf der man nicht Tangos wie „Comme il faut“, „Derecho viejo“, „Retintín“, „La Guitarrita“ oder eine andere der vielen Kompositionen Arolas zu hören bekommt.

Arolas war ein Bandoneon-Spieler und Komponist, der unter seinen Kollegen hohes Ansehen genoss. Er wurde 1892 in Buenos Aires geboren und verstarb im noch jungen Alter von 32 Jahren in Paris. Es gibt daher von Arolas und seinem Orchester relativ wenige Schallplatten und die wenigen, die uns erhalten blieben, sind primitive Aufnahmen mit schlechter Klangqualität.

Sein erstes Instrument war die Gitarre, die er in den Cafés seiner Heimatstadt spielte,. Er wechselte aber bald zum Bandoneon. Um 1909, als er seinen ersten Tango komponierte („Noche de garufa“), konnte er noch keine Noten lesen, und seine Freunde mussten ihm bei der Niederschrift helfen. 1911 trat er aber in ein Konservatorium ein und studierte dort für drei Jahre Musik. Das Studium schlug sich deutlich in seinen Kompositionen nieder. Seine Stücke—darunter auch Cardos—zeugen von einem experimentierfreudigen Komponisten mit guten Kenntnissen der Musiktheorie.

3. Cardos

Cardos ist einer von Arolas weniger bekannten Tangos. Uns sind zwei Aufnahmen bekannt, von denen eine, die wundervolle Version des Orquesta Típica Victor, unten als Beispiel angeführt wird. Da sich im Stück keine Spuren des Habanera-Rhythmus finden, ist anzunehmen, dass Cardos eine der späteren Kompositionen Arolas aus den 20er Jahren ist.

Wie die meisten instrumentalen Tangos aus dem ersten Viertel des 20. Jahrhunderts wurde Cardos in einer dreisätzigen Liedform komponiert. Die Struktur ist äußerst regelmäßig: jeder Satz (hiernach A, B, beziehungsweise C) besteht aus 16 Takten. Jeder Satz ist wiederum in einen Vorder- und Nachsatz von je 8 Takten aufgeteilt.

Diese Aufteilung setzt sich auch in den kleineren Bestandteilen fort: die acht-taktigen Vorder- und Nachsätze bestehen aus zwei vier-taktigen Perioden, und die Perioden ihrerseits aus zwei zwei-taktigen Motiven. Jede Periode endet mit einer Kadenz, von denen die, die am Ende der Nachsätze stehen, stärker sind.

Entsprechend der Vorzeichen und Schlussakkorde sind die Sätze A und B in D-Moll. In beiden Fällen geht dem Schlussakkord eine starke Kadenz voraus, die die Tonalität klar im D-Moll verankert. Satz C zeigt die gleichen Vorzeichen wie die anderen beiden Sätzen, endet aber mit einem F-Dur-Akkord, ebenfalls nach einer starken Kadenz. Dieser Satz steht also in F-Dur, der Paralleltonart zu D-Moll.

Wenn das Stück mit all seinen Wiederholungen gespielt wird (so wie in der Aufnahme des Orquesta Típica Victor, siehe unten), ergibt sich die folgende tonale Anordnung der Sätze:

Der formale Plan und tonale Zusammenhang ist durchaus konventionell. Satz C steht in einer anderen Tonart und wird durch die Wiederholungen von den anderen Sätzen umrahmt. Als ganzes gesehen beginnt und endet das Stück in D-Moll und wendet sich zur Abwechslung in der Mitte der kontrastierenden Tonart zu, der Paralleltonart F-Dur.

Wir haben oben festgestellt, dass es eine Eigenschaft der Paralleltonarten ist, sich mehrere Akkorde zu teilen. Es ist daher einfach, die Harmonie von einer Tonart in die Paralleltonart zu lenken. Das heißt, es ist nur ein kleiner Schritt, der vielleicht kaum bemerkt wird. Wenn aber die Abgrenzung zwischen parallelen Dur- und Molltonarten schwach ist, dann gibt es auch Raum für Zweideutigkeit. Es ist genau diese Zweideutigkeit, die Arolas in Cardos in den Vordergrund stellt und sein Stück interessant macht. Im Gegensatz zu dem ziemlich konventionellen formal Aufbau des Stückes ist die Entwicklung der Harmonie innerhalb der Sätze viel verwickelter und faszinierender.

Wir haben festgestellt, dass die formale Gliederung von Cardos sehr regelmäßig ist. Jeder Satz besteht aus 16 Takten, welche sich wiederum in acht-taktigen Vorder- und Nachsätze aufteilen, usw.

Der Vordersatz des Satzes A veranschaulicht die Aufteilung in vier-taktige Perioden besonders deutlich, da die erste und die zweite Perioden identisch sind. Takte 5 bis 8 sind eine Wiederholung der Takte 1 bis 4.

Wir haben oben festgestellt, dass es eine Eigenschaft der Paralleltonarten ist, sich mehrere Akkorde zu teilen. Es ist daher einfach, die Harmonie von einer Tonart in die Paralleltonart zu lenken. Das heißt, es ist nur ein kleiner Schritt, der vielleicht kaum bemerkt wird. Wenn aber die Abgrenzung zwischen parallelen Dur- und Molltonarten schwach ist, dann gibt es auch Raum für Zweideutigkeit. Es ist genau diese Zweideutigkeit, die Arolas in Cardos in den Vordergrund stellt und sein Stück interessant macht. Im Gegensatz zu dem ziemlich konventionellen formal Aufbau des Stückes ist die Entwicklung der Harmonie innerhalb der Sätze viel verwickelter und faszinierender.

3.1 Satz A

Wir haben festgestellt, dass die formale Gliederung von Cardos sehr regelmäßig ist. Jeder Satz besteht aus 16 Takten, welche sich wiederum in acht-taktigen Vorder- und Nachsätze aufteilen, usw.

Der Vordersatz des Satzes A veranschaulicht die Aufteilung in vier-taktige Perioden besonders deutlich, da die erste und die zweite Perioden identisch sind. Takte 5 bis 8 sind eine Wiederholung der Takte 1 bis 4.

|

| Cardos, Satz A, Vordersatz |

Der Nachsatz imitiert die Melodien des Vordersatzes mit unterschiedlichen Harmonien und ohne Wiederholung. Die Gliederung in vier-taktige Perioden ist dennoch beibehalten.

|

| Cardos, Satz A, Nachsatz |

Cardos, Satz A

In Hinblick auf die Tonalität unterscheiden sich der Vorder- und Nachsatz maßgeblich. Wenn man den Vordersatz für sich allein betrachtet, so ist es nicht offensichtlich, in welcher Tonart er entworfen wurde. Die beiden (identischen) Perioden setzen sich aus zwei einfachen Motiven zusammen: einem F-Dur-Akkord, einem D-Moll-Akkord und deren Dominant-Akkorde. Der harmonische Ablauf kann als F-Dur genauso wie als D-Moll ausgelegt werden. Ist der Vordersatz in F-Dur, dann beginnt er auf der Tonika (I)--ein gängiger Ansatz. Ist er in D-Moll, dann endet der Vordersatz auf der Dominante (V)—ein konventioneller Abschluss. Beide Interpretationen sind plausible, aber die Tonalität des Vordersatzes bleibt deshalb zweideutig.

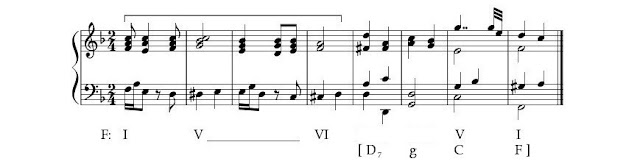

Das folgende Beispiel (die Musik wurde zu einer einfachen Akkordfolge reduziert) skizziert eine harmonische Analyse in D-Moll sowie F-Dur.

Das folgende Beispiel (die Musik wurde zu einer einfachen Akkordfolge reduziert) skizziert eine harmonische Analyse in D-Moll sowie F-Dur.

|

| Cardos, Satz A, Vordersatz, Harmonie-Reduktion |

Im Nachsatz wird der tonale Zusammenhang unmissverständlich hergestellt. Beide Perioden enden mit einer Dominant-Tonika-Kadenz in D-Moll (V-I, siehe Takte 3-4 sowie 7-8 ).

|

| Cardos, Satz A, Nachsatz, Harmonie-Reduktion |

Zusammenfassend läßt sich sagen, dass der Vordersatz tonal mehrdeutig ist und D-Moll als Tonart erst im Nachsatz festgelegt wird.

Cardos, Satz A, Harmonie-Reduktion

3.2 Satz B

Ein auffallendes Merkmal des Satzes A war die exakte Wiederholung der ersten Periode im Vordersatz. Ein ähnlicher Entwurf findet sich im Satz B, in dem die Wiederholung allerdings den ganzen Vorder- und Nachsatz einbindet. Darüber hinaus sind die Motive in einer anderen Form der Wiederholung angeordnet, nämlich als Sequenz. Alle zwei-taktigen Motive ähneln sich; sie werden aber nicht exakt wiederholt, sondern abwärts auf eine andere Tonleiterstufe verschoben.

|

Cardos, Satz B, Vordersatz

|

Der Nachsatz wiederholt den Vordersatz fast vollständig und ist nur am Ende melodisch verändert, um die Kadenz zu verdeutlichen.

|

Cardos, Satz B, Nachsatz

|

Cardos, Satz B

Analog zum Satz A findet sich auch in diesem Satz eine tonal mehrdeutige Passage. Die erste Periode im Vorder- und Nachsatz läßt sich nicht eindeutig einer Tonart zuschreiben.

|

Cardos,

Satz B, Vordersatz, Harmonie-Reduktion

|

Die erste Periode (Takte 1-4, zwei Motive der Kadenz) besteht aus einer harmonischen Progression (D-g-C-F), in der jeder Akkord eine Quinte (5 Tonleiterstufen) unter dem vorhergehenden liegt. Die Progression ähnelt so einer Folge von Nebendominanten, in der der vorhergehende Akkord im nachfolgenden aufgelöst wird. Da es sich um eine Serie von Dominanten handelt, fehlt ein direkter Bezug auf eine Tonika. Die Sequenz ist daher zweideutig und könnte als F-Dur oder D-Moll gedeutet werden. Erst in der zweiten Periode (Takte 5-8) wird Tonart durch eine starke Kadenz auf D-Moll festgelegt (Takte 6-8).

Die Sätze A und B stimmen in ihrer Tonart überein. Sie sind beide in D-Moll, aber die Tonart wird nicht am Anfang, sondern erst später nach einer tonal ambivalenten Passage eindeutig festgelegt.

Die Sätze A und B stimmen in ihrer Tonart überein. Sie sind beide in D-Moll, aber die Tonart wird nicht am Anfang, sondern erst später nach einer tonal ambivalenten Passage eindeutig festgelegt.

Cardos, Satz B, Harmonie-Reduktion

3.3 Satz C

Satz C setzt das Modell der Wiederholungen wie in den vorangegangenen Sätzen fort. Die beiden Motive der ersten Periode (Takte 1-2, sowie 3-4) wurden als Sequenz gestaltet.

|

Cardos, Satz C, Vordersatz

|

Wie in Satz B wiederholt der Nach- den Vordersatz fast vollständig. Nur am Ende findet sich eine melodische Variation zur Verdeutlichung der Kadenz.

|

| Cardos, Satz C, Nachsatz |

Cardos, Satz C

Satz C unterscheidet sich von A und B insofern, als die Tonalität früher und deutlicher festgelegt ist. Das ergibt sich einerseits aus der strukturell einfacheren Dur-Tonart (F), andererseits aber auch daraus, dass man die beiden Perioden des Vorder- und Nachsatzes als erweiterte Kadenzen in F-Dur auslegen kann.

|

Cardos, Satz C, Vordersatz, Harmonie-Reduktion

|

Die erste Periode (Takte 1-4) beginnt auf der Tonika (I), und führt dann über die Dominante (V) zu D-Moll (VI, Takt 4). Die Progression I-V-VI (Dominant-Kadenz mit Auflösung zur Paralleltonart anstelle der Tonika) wird „Trugschluss“ genannt und gehört zu den Standardformeln der Harmonielehre.

Die zweite Periode (Takte 5-8) wiederholt eine harmonische Kadenz aus dem zweiten Satz, nämlich die harmonische Sequenz der Nebendominanten D-g-C-F. Im Satz B erschien diese Akkordfolge in der ersten Periode. Hier wurde sie in die zweite Periode versetzt. Die Analogie geht weiter: die erste Periode im Satz C endet mit einem Trugschluss in D-Moll. Satz B schließt in der zweiten Periode mit eine D-Moll-Kadenz. Der Komponist rekapituliert also im Satz C die Harmonien aus Satz B, überkreuzt aber die Reihenfolge der beiden Perioden.

Die zweite Periode (Takte 5-8) wiederholt eine harmonische Kadenz aus dem zweiten Satz, nämlich die harmonische Sequenz der Nebendominanten D-g-C-F. Im Satz B erschien diese Akkordfolge in der ersten Periode. Hier wurde sie in die zweite Periode versetzt. Die Analogie geht weiter: die erste Periode im Satz C endet mit einem Trugschluss in D-Moll. Satz B schließt in der zweiten Periode mit eine D-Moll-Kadenz. Der Komponist rekapituliert also im Satz C die Harmonien aus Satz B, überkreuzt aber die Reihenfolge der beiden Perioden.

Cardos, Satz C, Harmonie-Reduktion

4. Résumé

Unsere Analyse deutet an, dass die Entfaltung der Tonalität in Cardos sorgfältig entworfen wurde. Sätze A und B wurden in D-Moll gesetzt, während Satz C in der Varianttonart F-Dur erscheint. Im Vergleich zum klaren F-Dur in Satz C ist der harmonische Ablauf in den vorangehenden Sätzen komplexer. Eine eindeutige Festlegung der D-Moll-Tonart erfolgt nach Passagen, die tonal mehrdeutig sind. Satz C ist dagegen von Anfang bis Ende eindeutig in F-Dur, und damit stellt das Trio einen tonalen Gegensatz zu den anderen beiden Sätzen dar.

Arolas' Cardos ist eine faszinierende Komposition, die durch eine Bescheidenheit der Mittel überrascht. Der Komponist entwarf ein Stück mit einer Handvoll melodischer und harmonischer Ideen und entwickelte sie mit großer Ausdruckskraft zu einem eindrucksvollen Musikstück. Cardos ist das Werk eines erfahrenen Komponisten, der sein Stück mit Umsicht und Überlegung ausarbeitete. Nichts erscheint dem Zufall überlassen. Arolas Ruhm als Bandoneonist ist legendär, aber eine Einschätzung als Komponist steht noch aus. Soviel deutet Cardos an: Er war ein ernsthafter Komponist, der durchaus ernst zu nehmen ist.

Eduardo Arolas: Cardos, Orquesta Típica Victor

© 2017 Wolfgang Freis