As we have seen in Part 1 of our discussion, Iradier's La Paloma and El Arreglito were classified as canción americana and canción habanera, respectively. In addition, Iradier's “American” compositions include yet another category besides the danza habanera, namely, tango americano.

The origin of the term “tango” and what kind of music it referred to has not been unambiguously clarified. What is clear is that “tango” was not a new term when Spanish composers, like Iradier, began to write pieces by that name in the mid-nineteenth century. Looking at the scores one wonders, in fact, what distinguishes a tango from an habanera, for example. This is particularly striking in the work of Iradier: all of his “American” pieces, including the danzas, are vocal compositions, are built on the habanera rhythm, and show the typical melodic cross rhythms we have encountered in La Paloma and El Arreglito.

However, it is not only in Iradier's work that such ambiguity of categorization can be detected. Tangos and habaneras were written for stage works and instrumental music, with no consistent differentiation. One has to content oneself with the realization that composers handled the categorization of their pieces quite casually.

For example, La Flor de Santander (1861) a tango composed by Dámaso Zabalza (1835-1894) is a piano piece that shows correspondences to the danza habanera La Cubana by Florencio Lahoz discussed in Part 1.

|

| Dámaso Zabalsa |

1. La Flor de Santander

Dámaso Zabalza was a concert pianist and piano professor at the conservatory of Madrid. A prolific composer of music for the pianoforte, his pieces included piano etudes, arrangements of operas, and dances popular at the time—among them “American” pieces like habaneras, contradanzas, and tangos.

His tango La Flor de Santander (88 measures) is a longer piece than La Cubana, but it is still a short composition. It consists of 4 sections plus an introduction. Fundamentally, each section is built on a 16-measure phrase. Only the antecedent phrase of section A has 2 “empty” accompaniment measures pre- and appended, respectively, which makes the phrase sound somewhat unbalanced. But apart from this little anomaly, the phrase structure of La Flor de Santander is very regular.

Section

|

Actual Length

(in Measures)

|

Fundamental Length

(in Measures)

|

Tonality

|

Introduction

|

8

|

c minor

| |

A

|

18

|

10 (8+2) + 8

|

c minor

|

B + bridge

|

20

|

16 + 4

|

Eb major → c minor

|

A (repetition)

|

18

|

10 (8+2) + 8

|

c minor

|

C

|

8 (16 with repetition)

|

8

|

c minor

|

D

|

16

|

C major

|

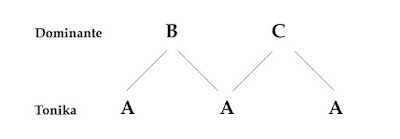

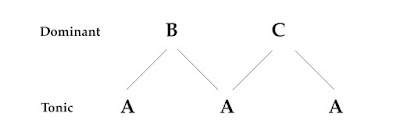

The composer also uses the tonal relationships of major and minor keys to express the formal structure of the piece. In El Arreglito, Iradier differentiated sections by alternating the parallel keys d minor and D major. Here in La Flor de Santander we also find parallel keys but employed differently: the piece begins in c minor but ends in C major. Furthermore, section B seems to shift tonally to the relative major key Eb major in the antecedent phrase, only to return to c minor in consequent phrase. This little shift to the relative major is nevertheless significant: it foreshadows the ending in the parallel major key.

Interesting are also the harmonic progressions of the last section. They may be described as two extended cadences, thus, as progressions that decisively establish the tonality in C major. The consequent phrase uses the more common subdominant, dominant, tonic progression. The antecedent phrase, however, introduces some harmonic color by moving through a series of secondary dominants. These secondary dominants are all major chords, and thus the progression from A major to D major to G major before resolving to the tonic C major. The contrast to the preceding sections could not be stronger. From the beginning up to section D, the piece is in c minor, only briefly leaning toward the relative major key. Section D is not only in C major, its harmonic progressions contain nothing but major chords.

We started our discussion of La Flor de Santander by suggesting that this tango exhibited correspondences to the danza habanera La Cubana by Lahoz. Both pieces are piano works, the phrase composition is similar (16-measure phrases, with slight irregularities), and the rhythmic structure of the melodies shows correspondences (cross rhythms, síncopa).

La Cubana has a simple musical design, namely, a two-part song form. It is not difficult to imagine the music as setting the strophe and refrain of a poem. La Flor de Santander, on the other hand, is a more complex formal structure that is based on an important concept of harmony: the relationship between parallel and relative major and minor keys. The piece starts in c minor and ends in the parallel C major key, after having “visited” the relative Eb major in between. This harmonic pattern shows that the composer was trained in harmony of Western music. More important to the point: it speaks a tonal language that would still be readily understood by the “old school” composers of Argentinian tango, like Villoldo, Firpo, Greco, or Arolas, who will be active a few decades later. (Readers of our A Short Harmony of Tango will recognize the harmonic progressions and principles of formal structuring discussed in this article.)

2. The Audience of Piano Music

Iradier dedicated many of his vocal compositions to (sometimes internationally) well-known singers. It was the custom for composers to dedicate a piece to a singer or musician in the hope of getting it performed. It was a move to help the sale of the music. When a piece had been performed publicly on stage, the publisher would list it on the title page as an advertisement. La Flor de Santander, however, is a simple piano piece, too simple to attract the interest of a well-known pianist and to be performed in a concert. Instead, it can be inferred that La Flor de Santander and similar pieces like La Cubana were intended for the greater audience of piano-playing amateurs.

The importance of easy-to-play piano pieces should not be underestimated. At a time without television, radio, or even the gramophone, one had to go the opera, a concert hall, or a café to hear music. Otherwise, one had to play it oneself. Piano music was sold as inexpensive sheet music or in modest collections. It was a powerful distribution channel through which new music reached a wide audience—not only in Europe, but also in countries of the New World.

This holds true for Argentinian tangos as well. In the early days of tango, when records were expensive and the radio not yet been invented, piano sheet music was the most important outlet for the dissemination of new compositions. Arturo de Bassi commented in an interview in the 1930s on his first great success as a composer. He wrote his tango El Incendio in 1906 when he was just 16 years old and worked as an orchestra musician at the Apolo Theater in Buenos Aires. The orchestra premiered the piece at the theater during an intermission. Since he could not find a publisher, De Bassi had El Incendio printed at his own expense and sold it on consignment in music stores. The piece became a hit and sold 50,000 copies.

This holds true for Argentinian tangos as well. In the early days of tango, when records were expensive and the radio not yet been invented, piano sheet music was the most important outlet for the dissemination of new compositions. Arturo de Bassi commented in an interview in the 1930s on his first great success as a composer. He wrote his tango El Incendio in 1906 when he was just 16 years old and worked as an orchestra musician at the Apolo Theater in Buenos Aires. The orchestra premiered the piece at the theater during an intermission. Since he could not find a publisher, De Bassi had El Incendio printed at his own expense and sold it on consignment in music stores. The piece became a hit and sold 50,000 copies.

The success of El Incendio was exceptional, and the sales total given by De Bassi must have been accumulative over the years. Nevertheless, the fact that an individual—an unknown composer, without the help of an established publisher—could sell a significant number of copies of a piano score bespeaks an interest and demand by the general public.

Our investigation of the development from habanera to tango has led us from the stage and musical salon, where professional musicians performed for an audience, to the private homes of music amateurs who purchased piano scores for personal entertainment and educational purposes. The producers of this kind of music were music professionals (composer, arrangers, publishers) who provided their audience with a huge body of piano music intended private amusement. This repertory consisted of popular music in the widest sense: piano reductions from stage works, songs, dances, and “American” pieces, like habaneras, tangos, or danzas cubanas.